Restoring the oyster resource

One reef at a time

By Hannah Miller

For North Carolinians, one of the pleasures of the chilly months is to sit down before a plateful of oysters straight from our coastal waters. At Carteret County's T &W Oyster Bar, which owner Earl Taylor says is on NC Hwy. 58 "out in the middle of the county in no man's land," they go through 60 bushels a week.

"We start shucking as hard as we can, and they start pigging out," says Taylor, a member of Carteret-Craven Electric Cooperative. "It's a nice-looking sight in here when I've got 40-something seats and a person on each one of them. We're rocking and a-rolling."

For many years, the forgotten ingredient in all this chowing down was the oyster shell. Spiny and rough-edged, it was a mottled black and gray lump that ended up in garbage dumps, chicken feed and driveways.

In the last decade, however, many of those North Carolinians have been collecting the shells to go into oyster reefs to grow more oysters. And much of the growing is going on in areas served by the state's coastal electric cooperatives. The effort is led by the Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF) of the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Several environmental groups and individual volunteers also help return the shells to the state's estuaries.

Oyster larvae float with the tides until they find a hard surface to attach to, and old shells are their favorite spot for launching into adulthood. "When we see those little spat (young oysters), we're so excited," says Allie Sheffield, a member of Jones-Onslow EMC and, as director of environmental advocacy group PenderWatch, an avid recycler. "We think they're beautiful."

They will grow into adult oysters with the ability to filter 25 to 50 gallons of water a day of sediment and other foreign materials.

Almost immediately after the shells have been dumped overboard by DMF barges, "fish and crabs flock to them. That's a hiding place for them," says biologist supervisor Clay Caroon, a member of Tideland EMC who is in charge of DMF reef-building. "As the oysters grow, that creates more crevices, more cracks, more hiding spaces," he says. "It also creates jobs."

Most of the shells go into areas where they're hand-harvested or collected with tongs. "These fishermen take their harvest to market," Caroon says, "the market sells them to restaurants, the restaurants sell them to a customer."

Earl Taylor at T & W Oyster Bar says he's already buying oysters from reefs built with recycled shells. "It might be the best government program I've seen or know of."

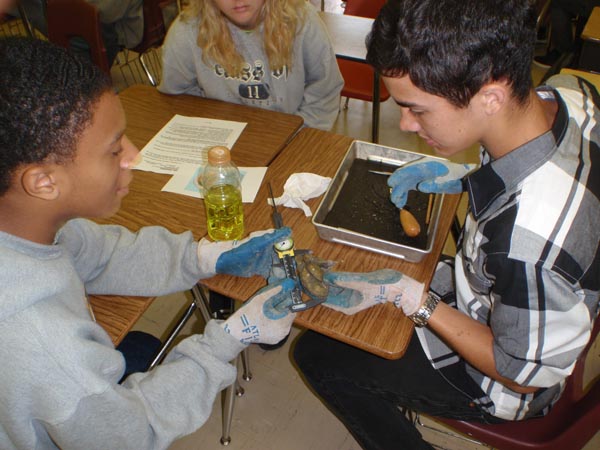

Students at Dixon High, a member of Jones-Onslow EMC, measure an oyster before dissecting it. (Photo courtesy of NCCF)

Recycling shells, building reefs

For years, the DMF has been building reefs from Dare County in the north to Brunswick County in the south, mostly using purchased shells. North Carolina's commercial oyster harvest has been gradually increasing, and Caroon gives part of the credit to the 25 to 40 reefs built a year.

Shell recycling, now under the direction of coordinator Sabrina Varnam, began in 2003. In the years since, dedicated volunteers at restaurants, oyster roasts, public and private waste collection services and family dinner tables have given the DMF 133,766 bushels. That's enough, at one square yard per bushel, to cover an area nearly the size of 21 football fields.

Collections, which are helped along by a state law banning disposal in landfills and a state tax credit of $1 per bushel for recyclers, have leveled off at about 20,000–25,000 a year, says Caroon. The DMF stockpiles them and uses varying amounts per year: in 2010 they were 6 percent of shells used, in 2009 18 percent.

Even inland restaurants take part, like Squid's Restaurant and Oyster Bar and its sister restaurants in the Chapel Hill Restaurant Group. "We really believe that we live in a world of limited resources," says partner Greg Overbeck. Before Orange County's landfill started setting aside a spot for shell recycling, he took them to a seafood dealer in Carrboro, who delivered them to DMF on his buying trips to the coast.

The next generation

Caroon, a fan of recycling, says he'd rather have the shells in the state's waterways than in landfills and driveways. But to keep them headed there, restaurants and other recyclers are going to have to take a more active role in consolidating loads. Recent state budget cuts have left only enough money for limited pickup, and no money for expansion, he says. "It's going to take some creative thinking and some good coordination."

Phoebe Hood, a retired nurse practitioner in Hampstead, carries shells for a PenderWatch reef.

That's just what a teacher and her students at Lakewood High School in Sampson County have been exhibiting. Stephanie Grady, a member of South River EMC, is passionate about the environment, and when she took her students to a Varnam presentation on recycling, "My kids saw it and said that was something they wanted to do."

Using material donated last year by Lowe's Home Improvement and Waste Industries, Inc., they built a 500- bushel bin to hold consolidated loads at the Sampson County regional landfill. One Saturday each month, she and the students empty two smaller containers they've set out and truck their contents to the wooden bin, which accepts other contributions from the county's residents and is emptied by the state in the spring. Students were so proud of their bin that they asked to build another, she says. "If we can find another spot or if another county wants to do it, we'll go build a bin for them."

In Pender County, the environmental advocacy group PenderWatch involves volunteers of all ages in collecting and bagging recycled oysters, then building reefs with them at the mouth of a river near the Inland Waterway. They started when they discovered there were no plans for DMF reefs in the area, and now, Sheffield says, moms and kids and seniors sign up.

Coastal restoration efforts by the N.C. Coastal Federation include an Oysters in the Classroom program at six schools in Carteret, Craven, New Hanover and Onslow counties. Students learn about oysters by dissecting them. After in-class instruction, they bag shells, some of them the recycled variety from DMF, and join in the federation's reef-building and reef-monitoring efforts.

Dixon High School teacher Gregory Batts, a member of Jones-Onslow EMC, laughs that he's lived near the coast all his life but never before realized that an oyster has a heart and an esophagus.

A couple of Dixon students, brothers Devin Hewitt, 15, and Dustin Hewitt, 14, learned recycling early from their father, Tony, a member of Jones-Onslow EMC. He's lived near Alligator Bay in Sneads Ferry for 11 years, and, he says, "I watched that bay grow from full of oysters to really not a lot."

Many of their neighbors are part-time residents who don't know how to collect oysters, the boys say, so they do it for them, asking customers to return the empties for recycling. "I walk the bank, pull my little boat behind me and throw them in the boat," Devin says.

"He'll go get the oysters and bring them back, and I'll cull them," says his brother Dustin. "I'll break the old shells off of them, throw them back in the bay to reproduce." Then they toss in customers' empties.

They're not alone in their interest, says Batts. "A lot of the kids enjoy taking care of the water."

This PenderWatch reef is ready to start serving as a home for young oysters.

-

Share this story: