Roanoke: The Persistent Mystery of a Lost Colony

The fate of the 1500s English colony is still up for debate

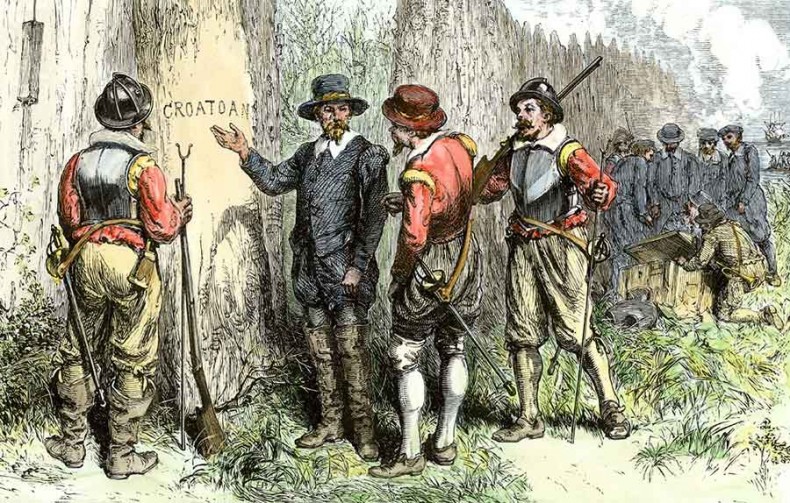

By Donna Campbell SmithJohn White reads what was a pre‑planned signal if the colonists had relocated.

In the fall of 2016, North Carolina’s lost colony wandered back into the nation’s attention. The familiar Roanoke mystery became the setting of a TV series, “American Horror Story.” The show’s sixth season (available to stream on Netflix) portrayed the first attempt to colonize the new world in the 16th century. But this retelling portrayed the history as a bizarre ghost story.

That version of the story is news, as far as locals know. Those interviewed don’t know of any such legend. (What’s more, the show was filmed in Los Angeles, rather than the Carolina coast. Some scenes show mountains in the background.) In spite of those drawbacks, the series received good ratings.

For those of us who’d like to let folks know the real story of the Lost Colony, well, that can be a little tricky. No one is sure what happened to the first English settlement in the New World. That's what makes the story so intriguing.

What we know

In April 1587, John White was sent with 117 men, women and children to colonize the New World. A previous attempt by Sir Walter Raleigh had failed. They meant to settle in the Chesapeake Bay area, but stopped at Roanoke Island to look for 15 men left behind by Raleigh’s previous colony. The ship’s captain had abandoned them on the island. White learned that two of the 15 had been killed in an attack by the Secotan Indians, and the remainder had fled. No one knows what happened to them.

Later, John White left Roanoke Island for England to resupply. When he arrived he found his ships were needed on the homefront because England was at war with Spain. He had no way to go back to Roanoke Island with the supplies.

When the war ended in 1590, John White finally returned to America. He found the colonists gone and the island deserted. The only clue left was the word “CROATOAN” carved on a post and the letters “C-R-O” carved into a nearby tree. This actually was a predetermined sign agreed upon by the settlers and White should they move before his return.

But White never confirmed their whereabouts, and as time passed, theories about the colonists’ fate have run the gamut. Here are a few.

Theory 1: A tragic fate

One intriguing story was told to me by Mary Hampton, the granddaughter of Thomas B. Shallington. Shallington was a Tyrrell County native. In 1938, while surveying near an old graveyard on the south side of Alligator Creek, he found a stone that measured 26 inches long and weighed about 100 pounds. Here is what was so interesting about this stone: On it was inscribed “Virginia Dare, B. Aug 1587, D. 1597.”

Robert W. White details the findings of other “Dare stones” in his book, “A Witness for Eleanor Dare,” and briefly mentions the Shallington stone.

In his book, White chronicles the discovery of a similar stone found on edge of the Chowan River in 1937 by Louis Hammond. He writes of other stones found in various locations, including near the Cape Fear River. These stones were inscribed with an account of an Indian attack and capture of the assumed inscriber, Eleanor Dare. She was the daughter of the colony governor John White and mother of Virginia Dare, the first English child to be born in the New World. The messages on the stones lead believers to the theory that most of the colonists were killed, and some taken captive, by local Native Americans.

Theory 2: Assimilation

An opposing theory speculates that the colonists and those native to the area lived together in harmony until, through intermarriage, they blended into one people. Evidence of this can be supported as English and native artifacts have been found in various archaeological digs along the North Carolina coast and the eastern mainland.

There is also written documentation of native people with phenotypical characteristics of Europeans, such as blue eyes and light hair, who lived on the coast, supporting the assimilation theory. These theories place colonists in various locations, including Virginia, the entire coast of North Carolina and some points inland. New information surfaces from time to time as archaeologists keep digging into the mystery.

In his book, “Touring the Backroads of North Carolina’s Upper Coast,” Daniel W. Barefoot described the finding of English and American Indian artifacts in the community of Beechland, located in the inland portion of today’s Dare County (formerly Tyrrell County). In 1956, workers for the West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company were building logging roads and canals in the area. They dug up a large mound. In examining the dirt dug up by their equipment, they discovered Indian arrowheads and pottery pieces. More astonishing, however, were the makeshift coffins: two dugout canoes lashed together. On the tops of the coffins were inscriptions of a cross and the letters “INRI.” The workers were commanded to re-bury the graves and continue with the tasks at hand. The land later was leased to the U.S. government to be used as a bombing range (likely destroying evidence of what might have held the key to the mystery of the Lost Colony).

Hatteras Island has given up clues making archaeologists believe the English colonists lived on the island with the Croatoan Indians. Digs have produced English artifacts dating to the 1500s, including a rapier handle, a slate writing tablet, pipes, a gold ring (later found to be brass and likely unrelated to the colony), bits of glass and sewing needles.

Thomas Shallington found what is believed to be a Roanoke colony clue while doing survey work in 1938.

Theory 3: Inland relocation

Another theory puts the colonists in Bertie County, 57 miles inland from Roanoke Island. The fact that John White instructed them to move that distance before his departure to go back to England seems to further support that theory. This belief is based on the hidden image of a fort on a 16th century map of the area.

Jeff Hampton of The Virginian-Pilot newspaper reported the finding of English artifacts dating to the late 1500s in the area by Fred and Kathryn Willard. They’d found pottery pieces of both English and Native American origin, as well as stone tools and arrowheads by the handful, on property just off Highway 17 along the Chowan River near Edenton. This is the same area Louis Hammond found the inscribed stone in 1937.

Theory 4: Island relocation

Scott Dawson, who founded the Croatoan Archaeological Society with his wife, Maggie, disputes the Bertie County theory. He believes documentation and archaeological evidence supports the theory that the colonists sailed 50 miles south, not west, from Roanoke Island to join the friendly Croatoans on Hatteras Island. He believes the Bertie County fort on the map was never built, which is why it was covered up and “hidden” on the map.

The wild card

Whatever may have happened to the colonists, the fate of the 13 men from the previous voyage remains a mystery. According to what the Croatoans told John White, the group escaped the Secotan attack. Perhaps these 13 escapees factor into some of the other theories, and it was those men from the previous colony who left what seem to be clues on the Carolina and Virginia sites.

It all remains a mystery, and good fodder for the imagination. Who can blame the producers of “American Horror Story” for borrowing from our legend to weave a story of their own?

This writer just wishes they could have replaced the mountains in the background with some sand dunes.

-

More Carolina History and Mystery

-

Share this story: