The Battle of Hatteras Inlet

An important event early in the Civil War that histories often ignore

By Michael E.C. Gery

There were lots of Yankees on Hatteras Island at this time of year 150 years ago, but they were not tourists and they were not on vacation. Many of them had arrived the summer before with the U.S. military invasion that in late August 1861 engaged in the first combined forces battle of the Civil War, resulting in the first Federal military victory over the Confederacy. They were still here the next summer occupying — sometimes uneasily — Hatteras Island. They lived in the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse keepers' quarters, in local houses, in barracks and camps.

The local residents — about 1,200 in all — by summer of 1862 had grown familiar with the occupying troops, who stayed for the duration of the war. There are reports of Federal soldiers and local people socializing, fishing together, attending church together. Many local men, in fact, had become Federal soldiers themselves, having joined the First North Carolina Union Infantry. Hatteras residents, by and large, had been indifferent to the war all along, having no real reason to rebel. So when the Union Army offered them clothing, food and a paycheck, young men did not hesitate to enlist.

Last year, a major symposium, "Flags Over Hatteras," had been organized to take place on the island in August commemorating the war's sesquicentennial and the events of August 1861. August 2011, however, saw a more familiar invasion on the Outer Banks. Hurricane Irene forced postponement of "Flags Over Hatteras" until April of this year, when it occurred during four days in lovely spring weather. An intrepid local committee, chaired by Drew Pullen, an island resident and author of two books about the Civil War on the Outer Banks, rescheduled the events, including presentations by prominent Civil War historians. At the same time, two historic markers were dedicated in Hatteras Village to acknowledge the events of August 1861. In a keynote address, James. M. McPherson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of more than 18 books on the war era, pointed out that while the Hatteras experience was of major importance, very few students of the Civil War know anything about it.

What happened at Hatteras

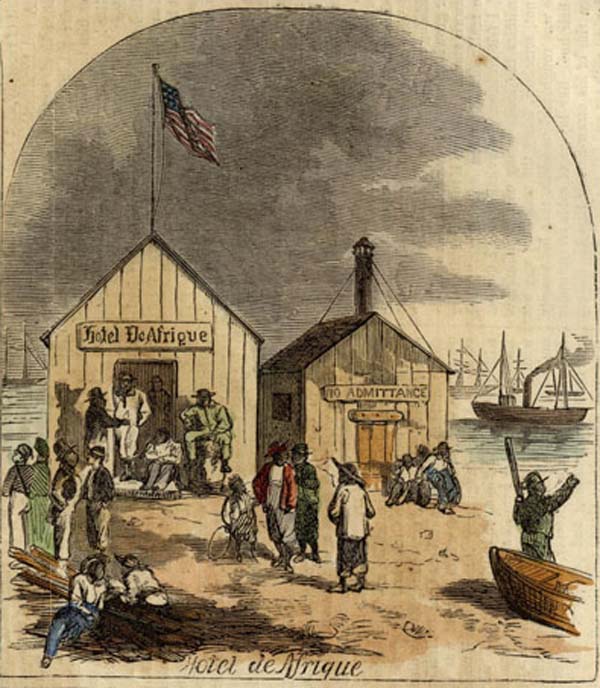

After the battle, slaves reached Hatteras for sanctuary. They built housing and a community referred to as “Hotel DeAfrique.” Illustration from the Feb. 15, 1862 edition of Harper’s Weekly.

On May 20, 1861, four months after voters rejected the idea, North Carolina's state government seceded from the union to join the Confederate States of America. Earlier, on May 9, Confederate troops and slave laborers began arriving at Hatteras to build and arm two earthen forts at Hatteras Inlet on the south of the island: Fort Clark facing the ocean, Fort Hatteras facing the inlet. They were meant to guard Hatteras Inlet, a main port of entry and supply route to the interior. And, as Hatteras historian Danny Couch pointed out, "On the ocean out here, it was like I-95. Between 200 and 1,000 ships would pass by here every day." Occasionally, a ship unable to navigate the shoals and storms off the Outer Banks would run ashore and, as Couch said, "it was like having a Wal-Mart turn over on the beach." But more often at the time, private vessels operating here, known as "The Mosquito Fleet," sometimes tipped off by unscrupulous northerners in the know, would chase and bring in northern-owned merchant ships with remarkable success. The ships' insurers didn't like that and helped persuade the Lincoln administration to send an expedition of combined Navy, Army and Coast Guard units to put a stop to the "rebel privateers" working out of Hatteras Inlet.

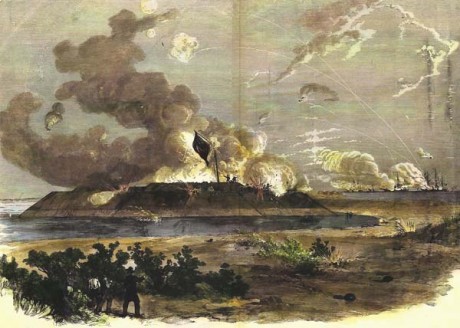

An impressive flotilla of seven warships, two transport vessels and a tug, with 143 big guns and some 880 troops — the largest naval force ever assembled in U.S. military history to date — left Hampton Roads, Va., on Aug. 26. On the morning of Aug. 28, the ships opened fire on Fort Clark. Simultaneously, more than 300 men were ordered to go ashore three miles north of the fort. An African-American crew on the massive flagship Minnesota manned the guns that shot first. Totally overwhelmed, Fort Clark's men soon gave up, lowered its flag, and fled to Fort Hatteras. Meanwhile, the Union troops heading for shore met unruly surf that broke up their boats, but they managed to land along with their two cannons. In soaked woolen uniforms, as Drew Pullen describes it, they trudged down the beach in sweltering heat, slogging through the sand, and finally reached the abandoned Fort Clark where they raised the Stars and Stripes. The next morning, Aug. 29, the Union ships shelled Fort Hatteras, whose guns were as feeble as those at Fort Clark, and forced its surrender in a few hours. Some 700 Confederate troops — "many of them farm boys from the Hertford area," said Danny Couch — fled. Most were soon captured and shipped off as prisoners. Thus ended the battle of Hatteras Inlet and the beginning of the Federal occupation of the island.

Uncertain how they would be treated, local residents fled to the woods or barricaded their homes against the plundering that followed. Some fled the island, including local leader John W. Rollinson, who was the Collector of the Port. The day after Fort Hatteras fell, residents presented the command with a plea to "allow us to return to our homes and property and protect us in the same as natural citizens, as we have never taken up arms against your Government, nor has it been our wish to do so. We did not help by our votes to get North Carolina out of the Union. ... " Indeed, many citizens took an oath of allegiance to the United States, joined its Army, and sought protection when the Confederates tried to re-take the island later that fall.

Immediately after the Union victory, slaves sailed themselves to Hatteras where they were given protection. They built housing near the forts, a placed dubbed Hotel DeAfrique, the first slave sanctuary of the war and the precursor to the larger Freedman's Colony on Roanoke Island. Maybe 100 strong at one point, more than a few stayed on the island and worked for occupying troops.

A major morale boost, the Union's first triumph at Hatteras led to further victories at Roanoke Island, Elizabeth City, New Bern and Fort Macon — all key to crippling the Confederate military in this part of the South.

-

Share this story: