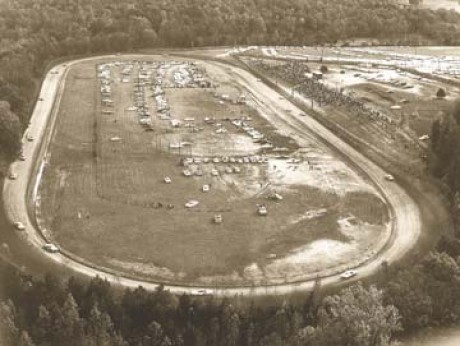

Kickin’ Up Dust Again at the Orange Speedway

35 years after Richard Petty won the last race here, the Occoneechee Speedway re-opened as a historic trail

By Sidney Cruze

Hillsborough native Carey Bateman was 12 when he saw his first NASCAR race at the Occoneechee Speedway in 1959. He and his friends waded across the Eno River, clamored up the bank, and snuck into the infield to see Cotton Owens and Lee Petty battle for first place. The speedway hosted two races each year, and for the next six years Bateman, a redheaded kid living across the river from the track's backstretch, saw them all. It was here that he first met Robert "Junior" Johnson, who nicknamed him "Red." Now, more than 40 years later, Bateman visits the speedway almost once a week. He is one of three trail stewards for the Historic Occoneechee Speedway Trail (HOST).

The 44-acre property sits on the National Register of Historic Places and is home to the only surviving speedway from NASCAR's inaugural 1949 season. A three-mile walking trail now crisscrosses the clay track carved out of the floodplain by Pontiacs and Oldsmobiles driven by the likes of Ned Jarrett and Fireball Roberts. The trail opened to the public in September 2003.

History of the Speedway

Located east of Hillsborough, the speedway site has a rich history dating back to the 17th century. The Occoneechee band of the Saponi Nation made their home here, living off the fertile ground and abundant wildlife of the Eno River Valley. In the late 1800s, General Julian Carr owned the land, and it became known as Occoneechee Farm. Carr raced horses and built a large barn and a half-mile racetrack on the farm. You can still see the gray stone walls that marked its grand entryway before it was subdivided into several smaller farms.

In the 1940s, NASCAR founder William France flew over Occoneechee Farm in one of his adventures as a pilot. From the air he could see the horse track and an expanse of open land along the river – the perfect venue for a mile-long automobile racetrack. France launched his new racing association in December of 1947, and in January of 1948 he purchased the land with help from Enoch Stanley and three other investors. By June of 1948 cars were roaring down the oval dirt track kicking up dust. The 20-year lifespan of the notorious Occoneechee Speedway had begun.

Leon Hutcherson was pit crew chief for Dick Hutcherson's 1964 Ford Galaxie 500 shown here at the Orange Speedway. © CAHPT

The NASCAR Strictly Stock Series, now the Winston Cup Series, was born in 1949. In April of that year, 17,000 screaming fans filled the stadium seats to cheer their favorite drivers to victory. As one of only three East Coast tracks measuring a mile, Occoneechee was a superspeedway. The distance allowed drivers to go faster here than they could on the shorter tracks. So fast, they often careened out of control, landing their cars on the riverbank. Non-paying onlookers climbed trees along the riverbank to get a glimpse of the spectacle.

The speedway closes

These Sunday NASCAR races were not popular with everyone in Hillsborough, and a group of citizens organized to stop them. They were successful, and on September 15, 1968, the black-and-white checkered flag fell for the last time behind Richard Petty. Tracks that were longer, paved, and locally supported replaced the racecourse, known since 1954 as the Orange Speedway.

Thirty years later, the speedway attracted the attention of Preservation North Carolina, a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting North Carolina's historic sites, and Richard Jenrette, the preservationist and founding partner of the Wall Street brokerage firm Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, Inc. Jenrette's Classical American Homes Preservation Trust (CAHPT) owns Ayr Mount, a restored 1815 Federal period plantation that sits across the Eno River from the speedway.

In 1997, Preservation North Carolina bought the NASCAR site from the estates of France and Stanley with funding from the James M. Johnston Trust and Jenrette's Classical Preservation Trust, which took title to the land and placed it under conservation easements that will protect it from future development.

People visiting the speedway today will find sycamore trees growing 25 feet tall amidst the rusted tin walls that once housed the concession stand and ticket booth. Blackberry brambles cover the concrete stadium seats, and wildflowers bloom along the well-worn track. Walking to the river, they can get a glimpse of the fence "Red" and his friends climbed over to get into the races.

Bateman's hair is silver now, and he chuckles when he thinks back to those carefree days. For him, working as a trail steward is coming full circle. "When I was a boy, the Exchange Club ran the track's concession stand. Now I'm the president of the Exchange Club."

He's thrilled the track is being preserved. "Since we opened the trail I've been surprised by the number of people coming out to walk it. And I never thought things would grow like this." He looks up, and the bill of his maroon HOST baseball cap points to the sky. "It's like the trees have been here forever."

About the Author

Sidney Cruze is a freelance writer with an interest in North Carolina’s historic places. She lives in Durham.-

Share this story:

{ampz:Custom share for module}