The Road to Recovery

Communities are working together to turn the tide on the opioid epidemic

By Gordon Byrd | Photos by Mollie Tobias Photography unless otherwise indicatedKaren Wicker (left) is the executive director of the recovery center. NC-certified Peer Support Specialists Stephanie Heck (center) and Amy Locklear are in recovery, giving them a unique perspective to help clients.

It was bitter cold, and a misty rain dogged the line of people outside a nondescript building near Cape Fear Hospital in Fayetteville.

In an archipelago of outpatient doctors’ offices that cordons the hospital, Acadia Healthcare’s Comprehensive Treatment Center is frequented by professionals, stay-at-home parents, insurance agents, wounded veterans — no one has the same story, but all shared the same burden as they stood together in line one early December morning. All struggled with substance use disorders, a part of the nation’s ongoing opioid epidemic.

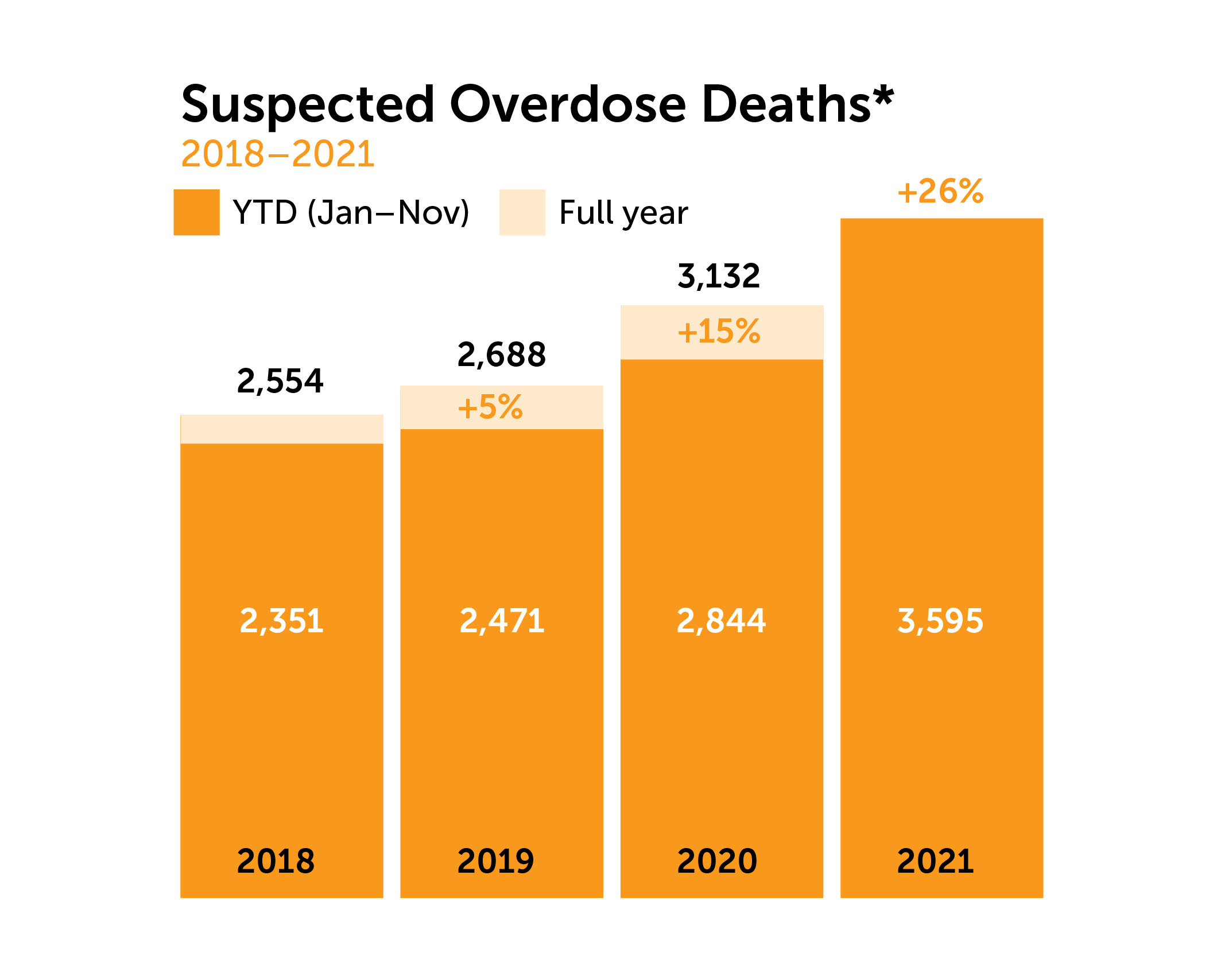

There are different paths to substance use disorder, and there are different paths to recovery, too.From 2000 to 2020, more than 28,000 North Carolinians lost their lives to drug overdose, according to the NC Department of Health and Human Services, and annual suspected overdose deaths continue to climb (see chart). But communities are banding together to help those in need, providing several potential paths to recovery.

From recovery to support

Louis Leake, clinic director at the Comprehensive Treatment Center — the largest opioid addiction treatment facility in the state — is a U.S. Army combat veteran, a pastor, and a sought-after speaker on the opioid crisis that has been gripping America’s society for over three decades. His office is small, tucked in the back of the building, but it gives him the opportunity to see each client pass as they exit. He knows many and has counseled more than a handful of them. No one demographic describes them. No archetypal story.

“We have three generations of families who attend our clinic,” he says, emphasizing that addiction to opioids is not limited to the young, or the poor, or the destitute.

Louis Leake, who often speaks on the opioid crisis, at the 2019 Opioid Misuse and Overdose Prevention Summit in Raleigh

Substance abuse is not limited to syringes or illicit drugs, either. “Prescription pain medications, opium, heroin and fentanyl are all opioids and affect the brain in essentially the same way,” writes Barbara Andraka-Christou, author of “The Opioid Fix.”

Louis was a paratrooper who logged more than 18 years of service and countless parachute jumps. Then, a parachuting accident left him paralyzed, with rods and screws holding his back and legs together. The pain medicine he was prescribed worked, though a creeping dependence was almost imperceptible.

“My pastor asked me to help the young men who were living in a halfway house our church ministered to,” Louis says in explaining his first step to realizing his addiction. “I heard these guys’ stories, and I thought: that sounds far too similar to my own story.”

Louis’ path to recovery was spiritual — as he puts it, he went on a spiritual retreat and came back different. He researched opioid addiction and began taking classes in a counseling program offered by the local community college. In recovery, he began counseling others.

Kennard Dubose, assistant professor in the Department of Social Work at UNC Pembroke, traces the history of addiction counseling from its earliest beginnings in Alcoholics Anonymous.

*Estimate of statewide medical examiner system overdose deaths; the majority become confirmed as poisoning deaths. Percent change represents year-to-date (YTD) suspected overdose deaths compared to YTD total of previous year, based on available data at time of publication.

Source: NC Office of the Chief Medical Examiner

“In the past, people in recovery were the counselors for others entering recovery,” he explains. The profession of substance abuse counseling has matured since then. Now certification programs are plentiful across the states.

Treatment centers have also proliferated. At first, abstinence-based treatments centers were the only centers available. Now, medicated assistant treatment centers are available in nearly every county of North Carolina.

Abstinence-based treatment programs follow a model that is similar to Alcoholics Anonymous’ 12-step program. The people in recovery stop taking the drugs, and work through withdrawal with counseling and support from peers. Medicated assistance treatments also involve counseling and peer support, but these treatment programs curb the symptoms of withdrawal by reducing their severity.

Both treatments work, but patients need to get to the treatment first. More local resources, as well as work to remove the stigma of substance use disorders, are making a difference.

Mobilizing community

Drug Free Moore County (DFMC), which has received funding support from Central Electric, the electric cooperative based in Sanford, is a nonprofit coalition with the mission of providing educational resources, treatment information and addiction recovery support. It was organized in 1989, but with the onset of the opioid crisis has ramped up its efforts from prevention programs for school students to providing recovery support to families who are affected by substance use disorder.

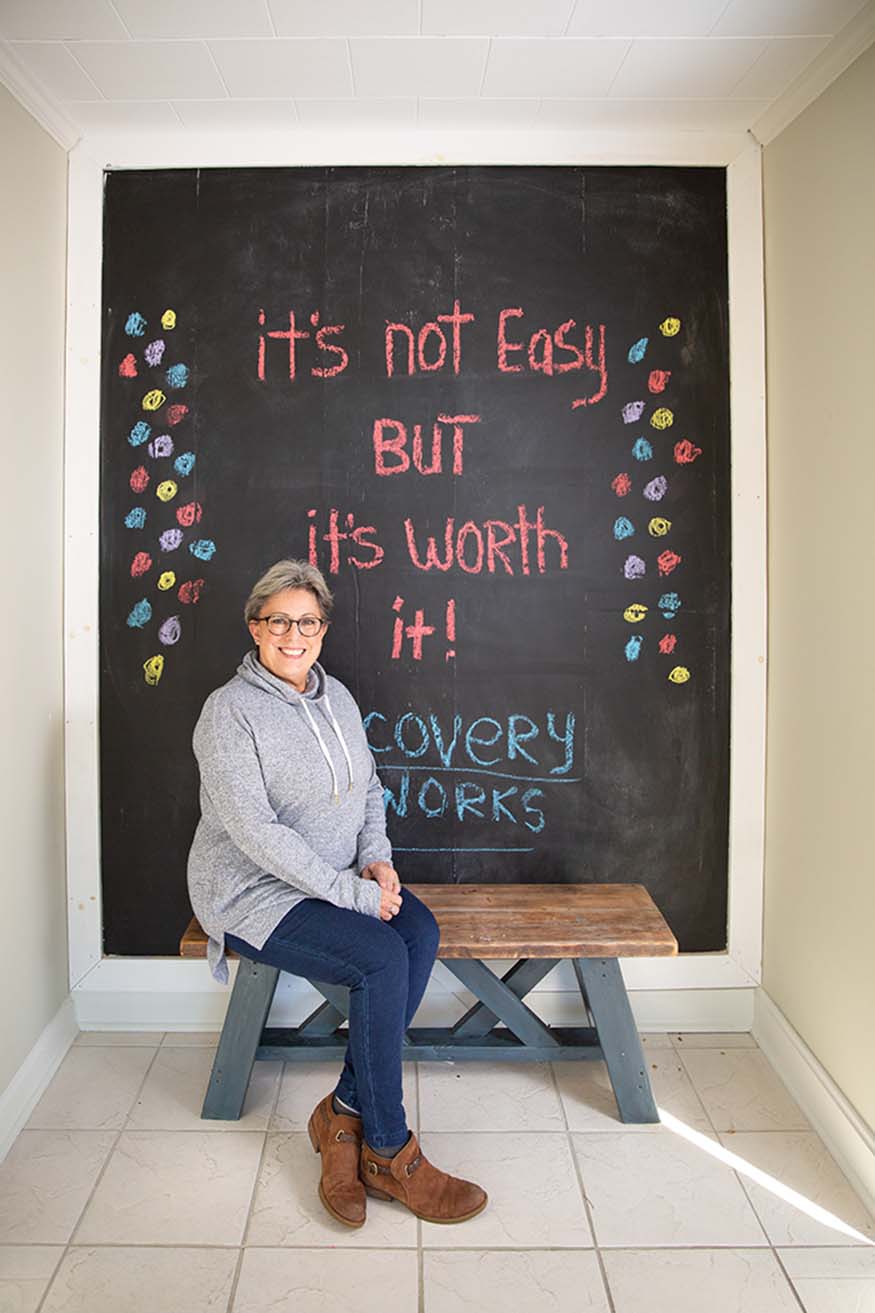

DFMC Director Karen Wicker recently opened a community recovery center called Moore ReCreations in Carthage to help provide a variety of support and resources to individuals and families. The center’s goal is to help individuals “recreate” themselves during their recovery.

Moore ReCreations provides peer support services, a safe syringe program, and recovery support groups in person and via Zoom through the Moore County Detention Center. Future plans include a family support group, a reentry support group for inmates, recovery yoga, a community garden, sewing classes and other opportunities for growth and healing. DFMC is also working to provide a medically assisted treatment (MAT) program at the center through a contract with a locally established MAT program.

Karen is no stranger to the ravages of the opioid crisis. Like many, she has personal experience with opioid addiction in her family. It started innocently enough, with her daughter’s adolescent anxiety issue bringing drugs into her life as doctor-prescribed treatment.

“This, combined with peer pressure and the grief suffered from the death of her brother when she was 18, started a slow but downward spiral,” Karen explains. “There are different paths to substance use disorder, and there are different paths to recovery, too. As a parent it is hard to pinpoint what is going on until something dramatic happens.”

For Karen, it was when she received one of the worst phone calls any parent could imagine: her daughter had been air-lifted to Chapel Hill following a head-on collision. Her status was unknown. It wasn’t until several weeks later they learned substances were involved.

“When my daughter had started treatment, we did not know that, unfortunately, relapse is a part of this disease. The journey of recovery wasn’t always easy or pleasant as a parent of a loved one suffering,” Karen says. Her daughter has started a new life after being in recovery for several years.

“Friends, family and people in general do not understand the heartbreak of not being able to help the one you love, or to even talk about it. Stigma is such a huge factor in families not getting the help and support they need.”

Taking the first step

The most important work is to remove the stigma of substance use disorders. For some, the perceived shame of addiction treatment keeps them from seeking help until it is too late.

Macon Moye, former vice president and general manager of WRFX’s John Boy and Billy network in Charlotte, first began taking pain medication for chronic knee pain. What was occasional use became daily, then became paired with alcohol. For years he refused to seek treatment until he was eventually hospitalized for more than three months.

“Two decades of drug and alcohol abuse takes a toll on your organs. They had shut down. Quit working,” he recalls of his 2012 near-death experience. Now, he is nearly a decade into recovery and supports others who are battling through recovery and the stigma associated with it through work at Chloe’s Place in Southern Pines (chloesplace.net) and at the Raleigh-based Welwynn Outpatient Center (welwynn.com).

Macon urges people who are suffering from a substance use disorder to seek treatment: “Life is too short to live dulled and desensitized.”

Seeking help

Are you or someone you know struggling with a substance use disorder? Contact the Alcohol and Drug Council of North Carolina at 800-688-4232 or alcoholdrughelp.org.

About the Author

Carolina Country Contributing Editor Gordon Byrd is a veteran who works for UNC Pembroke. While not working or writing, he spends most of his time with family and church.-

People helping people

-

Share this story:

Comments (2)

Alice Bell |

January 26, 2022 |

reply

Gordon Byrd |

February 07, 2022 |

reply