A Fresh Start for Rural Healthcare

Training the next generation of rural doctors

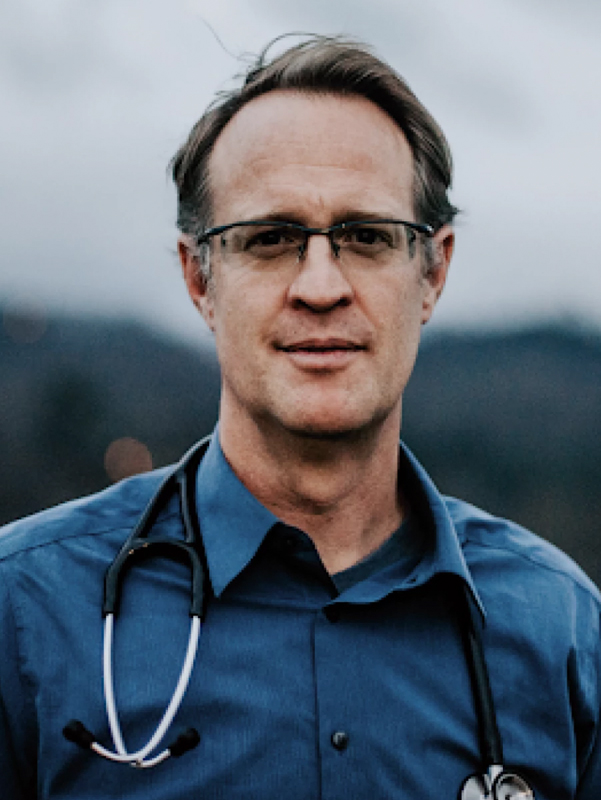

By Sarah Thompson | Photos by Corey Nolen unless otherwise indicatedBefore Cannon Memorial Hospital’s labor and delivery unit closed in 2015, Dr. Benjamin Gilmer delivered one of the last babies to be born in an Avery County hospital. The unit where his cousins were born is gone because it was no longer seen as cost-effective to provide obstetrical care in the county, Dr. Gilmer explains.

“We have had more labor and delivery closures per capita than any other region in the country,” Dr. Gilmer says. “This is bad for communities, bad for the economy and certainly bad for women who would like to deliver their child in their home communities.”

Dr. Gilmer is the medical director of the Rural Health Initiative and Rural Fellowship at the Mountain Area Health Education Center (MAHEC), the largest of nine area health education centers in the state, which address the supply, retention and quality of health professionals, particularly in rural communities. Before joining MAHEC, he lived and worked as a doctor in rural North Carolina. He believes that inspiring the next generation of doctors is the best way to help rural places not only survive, but attain health literacy and gain access to specialized doctors educated on social justice in health advocacy.

Counties in need

The North Carolina Institute of Medicine describes primary care providers as “the entry point into the health care system.” Access to their care is associated with fewer health disparities and better health among various socioeconomic statuses.

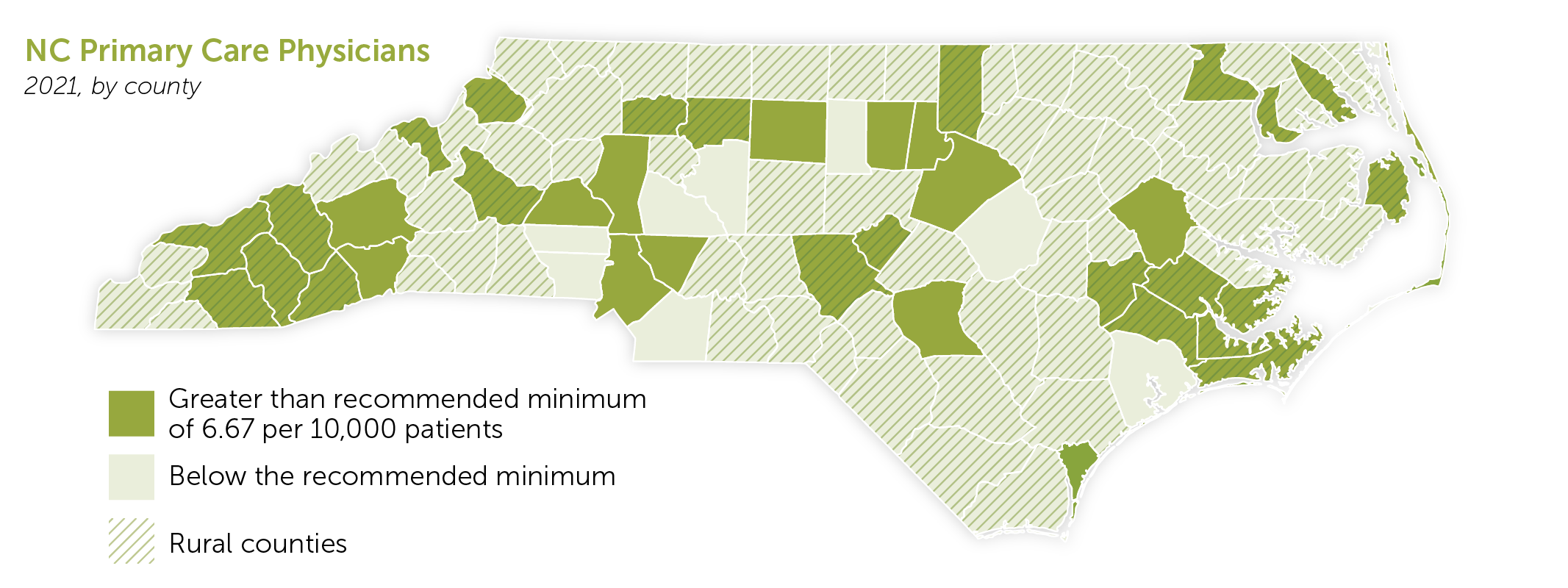

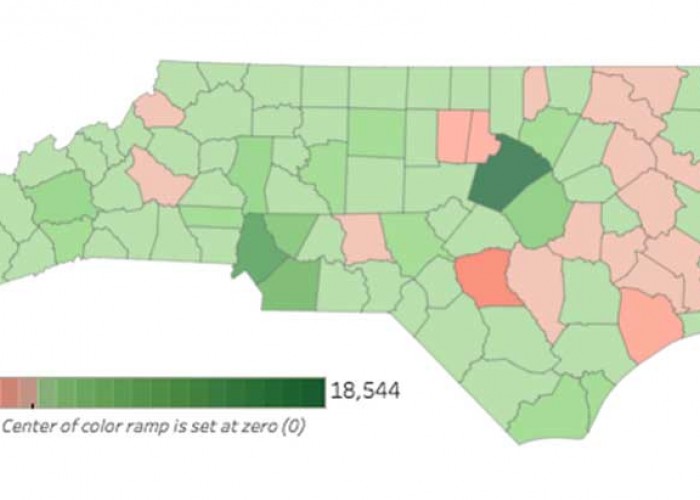

The target primary care provider to population ratio should be equal to roughly 6.6 providers per 10,000 patients, according to the Institute. This ratio symbolizes how access to providers improves overall health of communities and can prevent a diagnosis or injury from becoming a critical health issue. Yet many rural counties in North Carolina fall far short of this ratio (see map). The gap between access to health providers in rural versus urban counties is not just an inconvenience, it’s causing serious health disparities that doctors like Benjamin Gilmer want students to understand — and want to change.

NC Health Professions Data System

Rural training

Dr. Crystal Gaddy worked in rural healthcare systems for more than 18 years. She has witnessed its shortfalls firsthand. Today, she is an associate professor at Pfeiffer University’s Master of Science in Occupational Therapy program in Stanly County, where she and other faculty echo the significant need for students to practice medicine in rural areas.

“We’re able to, along with other faculty, really teach and educate our students with the hopes that they will, at least initially or at sometime within their careers, serve those who are really underserved,” Dr. Gaddy says. “From the moment the students enter Pfeiffer’s Occupational Therapy Program, that is the main focus.”

Pfeiffer University’s graduate program in Occupational Therapy (OT) began about two years ago alongside their Physician Assistant (PA) Studies program. As their brand-new building started construction and faculty got together to discuss curriculums, rural health was always a part of the conversation. The most pressing issue discussed was the shortage of health providers in rural regions.

Assistant Professor of Physician Assistant Studies and Randolph EMC member Dale Patterson says that it is extremely difficult to keep providers in rural places. When he’s not at the university, Dale continues to provide clinical care once a week in his local county, Montgomery. At Pfeiffer, students learn about the need for their skills in rural areas, but also the unique opportunities that practicing and living in a rural community can bring.

“The more rural you get, the more difficult it is to retain providers over time,” Dale says. “It can be burdensome on someone over a long period of time if you’re the only provider in office.”

Students discover this for themselves during their required fieldwork. Both the OT and PA programs place students across the country, and the world, to work with health providers and experience what it means to serve and be a part of a community. Dr. Gaddy believes that rural fieldwork is where students get the chance to show off their creativity and critical thinking.

“The best place to be creative is within rural healthcare,” Dr. Gaddy says. “When you have access to everything in the world, you don’t have to critically think as hard. With our students — with us trying to push them within those fieldwork areas and those opportunities in places we call ‘emerging areas’ — it shows them that anything is possible.”

Universities and rural health organizations try to motivate students to practice in rural areas through scholarships, loan forgiveness and other incentives. When Dale was in school, he received a National Health Service Corps scholarship and advises his students to take advantage of those opportunities, which give them more financial freedom to serve communities in need.

Desiring the work

Pfeiffer University

Graduate of Pfeiffer University’s Master of Physician Assistant Studies program, Samantha Gulledge is among those students who trained and are training to make a difference meeting the healthcare needs of rural communities.

Back in Western North Carolina, Dr. Gilmer works 60 to 80 hours a week trying to recruit the newest generation of doctors to practice in rural places. Over the past five years, they’ve placed approximately 30 doctors in western regions of the state. The Rural Health Initiative (RHI) has become the largest recruiter of the health professionals in the mountains and are busy looking to place more psychiatrists, general surgeons and obstetricians.

“Our ultimate goal is for every member of every rural community to have access to a primary care provider,” Dr. Gilmer says. “We want our students and doctors to desire work in rural areas.”

Like Pfeiffer, Dr. Gilmer advises students to look for avenues of support that can ease their transition into rural health systems. He explains the three pillars of support that RHI utilizes to attract and retain health professionals in western North Carolina. First, they talk with high school students to inspire them to give back to their community by becoming a rural care provider. Second, they recruit, train and support students through their schooling by providing scholarships, special training for rural care and connecting them with communities early on. Third, they support practices so that they feel well-capacitated and that they’re a part of a much larger mission.

Hope for the future

The work is exhausting yet rewarding. Doctors and local citizens are dedicating their lives to advocate and save lives in rural communities because they know everyone deserves the best care, no matter where they live. These advocates of rural healthcare find solace in those they work with and in the changes they’re seeing in the eyes of their students, patients and communities.

“Everybody wants to give rural communities the health services they need. It’s apolitical,” Dr. Gilmer says. “It’s more than medicine, and we’re just trying to do our part.”

About the Author

Sarah Thompson was a Carolina Country editorial intern in 2022. She is currently pursuing a journalism degree from UNC Chapel Hill.-

Rural Carolina

-

Share this story:

Comments (2)

Diana |

January 26, 2023 |

reply

Diana |

March 09, 2023 |

reply