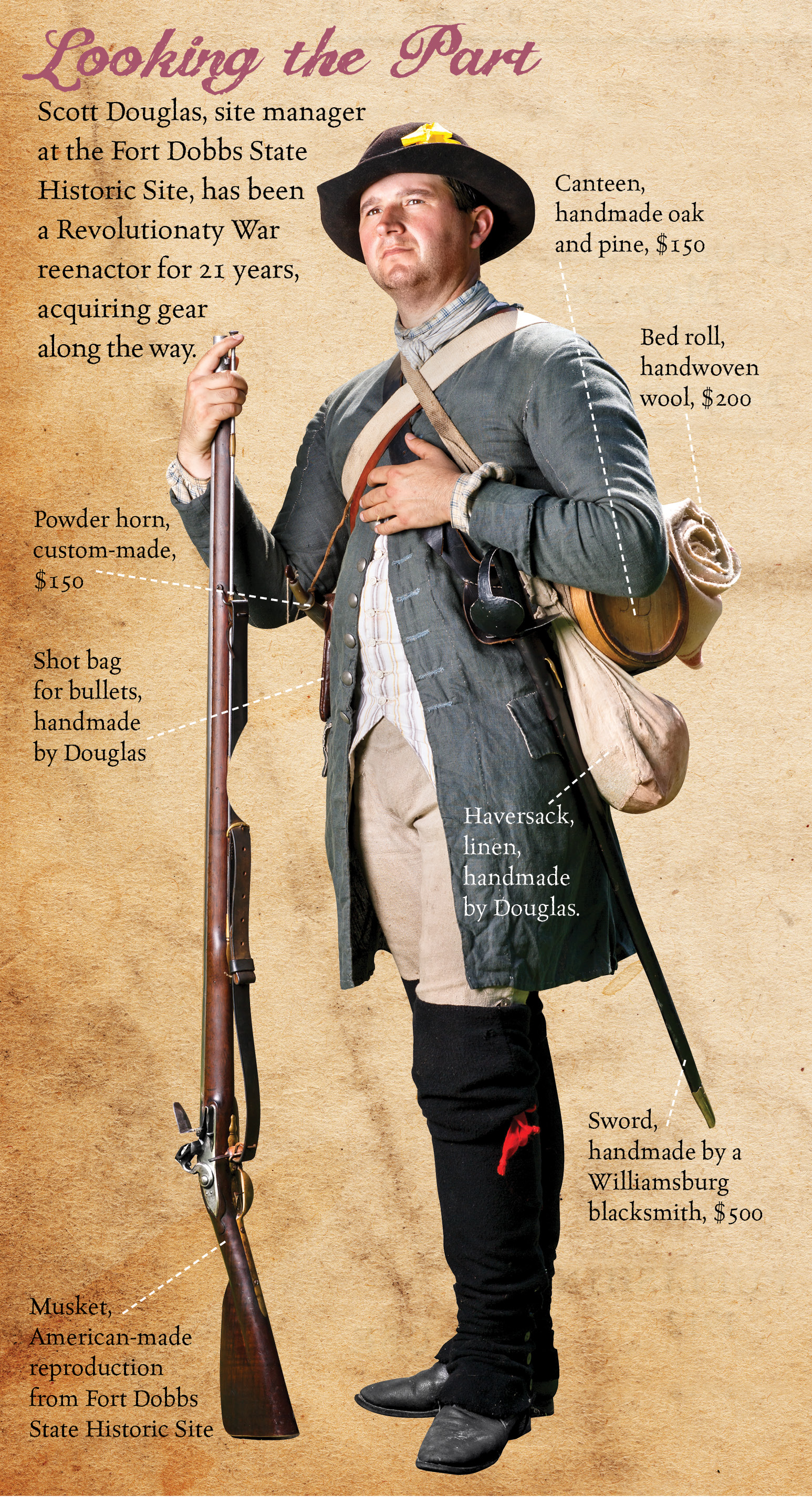

Reenactors Go All-in to Bring the Past to Life

Locals are drawn to the hobby through a passion for history

By Tina Firesheets | Photos by Perfecta Visuals

By 8 a.m., most are awake in the camp. Beds are made. Bacon sizzles in an iron skillet in front of the cook’s tent. Folks are getting dressed and finishing their first cup of kettle-brewed coffee. The air smells like campfires. Birds chirp and a rooster crows.

On this morning, the scene unfolding at the Alamance Battleground State Historic Site reflects a mix of time periods. Revolutionary War-era soldiers and camp followers are preparing for the day’s reenactment of the Battle of Alamance. They camped overnight in period-accurate tents or in the historic John Allen House, a log cabin there. At the edge of the historic property, there’s a row of colorful pup tents and a group of Boy Scouts in matching yellow T-shirts scattered across the lawn. Their playful shouts can be heard throughout the camp.

The battle itself is a few hours away. There’s time to smoke a pipe and sip a second cup of coffee. For now, enemies can be friends. It’s hard to distinguish between the two armies.

The Battle of Alamance

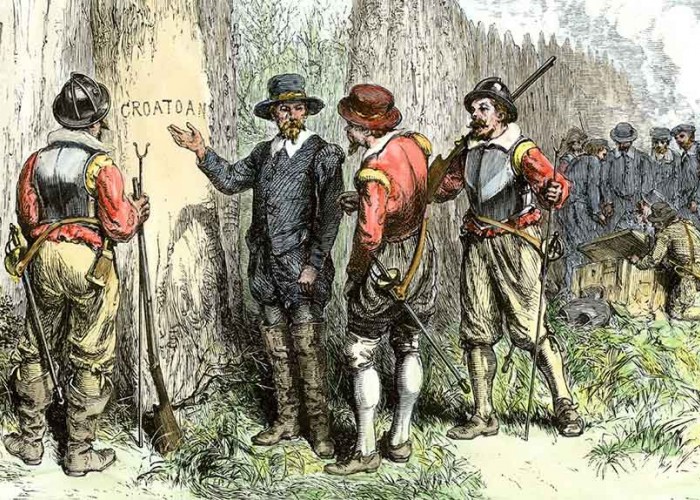

The “Fight for the Backcountry” occurred on May 16, 1771, involving a group of rebellious farmers known as the “Regulators” and a volunteer militia loyal to Royal Governor William Tryon. It was the peak of the Regulator movement, a five-year period in which rural farmers organized and demonstrated for better regulation of corrupt government officials. Peaceful attempts to enact change yielded to violence. In 1770, Regulators broke into the Hillsborough Superior Court, attacked lawyers and judges and demolished the home of a local leader. The Johnston Riot Act, adopted in 1771, outlawed Regulator leaders and retroactively made the Hillsborough riot an unlawful assembly.

In April, Tryon and his army left New Bern, marching west. The Regulators planned to block his advance, hoping to intimidate the Governor into meeting with them to address their grievances.

From Research Analyst to Royal Governor

Reenactors find their way to the hobby through their love of history.

David Snyder, who portrayed Governor William Tryon in the Battle of Alamance for the second time, began reenacting in 1976 after seeing a Revolutionary War reenactment of the Battle of Pell’s Point.

“I just had to do it. The uniforms, the muskets… the fifes and drums on the battlefield. Seeing the British troops march in formation and firing volleys of musketry. I really wanted to get in on that,” Snyder says. “It’s different to read about it, but to see it in front of you and smell the smoke was so vivid.”

He began reenacting as a private with the 64th Regiment of Foot, an infantry regiment of the British Army. He’s now a captain for the same regiment.

By profession, Snyder is a research analyst with the brain tumor immunotherapy program at Duke University Medical Center. To prepare for his impression of Governor Tryon, he assumes the mannerisms of a high-ranking British official. A friend used to describe it as “putting on an air of effortless superiority.”

His posture is more erect; his responses more measured. He softens his speech, and avoids modern words like “okay.” The cell phone stays hidden.

Prior to a reenactment, Snyder brushes up on Tryon’s biography so that the flavor of his personality becomes ingrained. When it comes to history, there’s always newly discovered evidence emerging, which maintains his interest, Snyder says.

He bears some resemblance to Governor Tryon, which makes the physical transformation easier.

“I can’t imagine not doing this,” Snyder says. “I’d have to be unable to walk anymore to not do it.”

Camp Laundress

Anna Kiefer is a second-generation reenactor, representing a minority on the field. She’s both a woman and a civilian. Some women traveled with armies, either following their husbands or joining for safety and rations. Kiefer portrays a laundress during Revolutionary War reenactments.

Kiefer bought a vehicle based on whether it could hold a wooden wheelbarrow and a 30-gallon copper kettle.

“The salesman thought I was nuts,” she says.“Everything has to fit in a special order, especially if I’m bringing my daughter (Shelby) to an event.”

The wheelbarrow goes in first, followed by the kettle behind the rear middle seat. Then the support poles for the kettle. The oak wash tubs sit inside the kettle. The tubs hold the tin pail with laundry supplies: hemp rope for the laundry line, soap, indigo, starch and laundry bags.

Finally, she packs her feather tick mattress, blankets, clothing and eating utensils.

It’s not unusual for her to actually launder clothing at reenactments, which are weekend-long and frequently hot.

“It’s hard work. It’s hot work and heavy work,” Kiefer says. “I don’t mind it, actually. I like it.”

A history teacher at Lord Fairfax Community College in Virginia, she says reenacting is another form of teaching: “Instead of teaching in a classroom full of college students, I’m talking to people of all different ages... it gives me an opportunity, as well, to teach people about a group of Colonial Americans who don’t often have a voice — women.”

Reenactments have led her to historic battlefields and sites around the country.

“To wake up on the actual Revolutionary War sites, it’s exciting,” she says. “It brings a level of reality to history.”

Feeding the Armies

A pork roast, rubbed with sage, salt, pepper and garlic, sizzles over an open fire. Juices drip into a pan below. Terry and Joe Ramsbotham planned quite a feast for the British and Regulator armies and their followers. Asparagus salad, with mustard vinaigrette. Vegetables, pickles and fresh bread. And macaroni and cheese, but not the elbow noodles of today’s mac and cheese. The macaroni Thomas Jefferson brought to America from France was flat and square. For dessert, they will have strawberry Charlotte, which is similar to cobbler.

The Ramsbothams work all weekend to feed the 50 to 60 reenactors. They serve what people would have eaten at the time in that season. Terry, a lifelong cook, has been a reenactor 22 years. Over a decade, she was an interpreter, baker, bakery manager and director of Historic Foodways and Gardens at Old Salem. The couple was asked to cook for an event at Fort Dobbs about 10 years ago, and has been cooking at reenactments ever since. They continue to streamline their operations. A large tent houses food and supplies for the weekend. It takes a couple of hours just to load the truck and trailer. Their Corgis, Abe and Bobbie, always accompany them.

N.C. State librarian David Serxner began assisting them recently. They haven’t had a lot of assistants, Terry says, because it’s such hard work: “You gotta love it, or you wouldn’t do it. When we lay down at night, we sleep.”

Terry says they love sharing their knowledge of Colonial food, and that people identify what they do with their grandparents’ traditions.

“I get to dress like this and research history,” Terry says. “And everybody likes food.”

Rick Sheets, a journeyman horner

Rick Sheets, a journeyman horner

Another Historical Hobby

Rick Sheets, a semi-retired website designer based in Durham, engages in a hobby with roots in very early American history.

Sheets, 62, has been shooting flintlock rifles, which fire with black gunpowder, since he was 14.

“Most guys my vintage, we kind of caught this bug by watching things like ‘Daniel Boone’ and ‘Davy Crockett’ on TV. The whole thing kind of resonated with me,” says the California native.

There are black powder shooter clubs and reenactments throughout the country. About nine years ago, Sheets was at a gunmaker’s fair when he met leather worker and horn maker Jeff Bibb, an artisan and guild master of the Honourable Company of Horners. The guild needed a website, and Sheets discovered a new passion.

Powder horns are typically made from cow, ox or buffalo horns. Sheets, who has artistic leanings, says horn making combined his interests: drawing, calligraphy, illuminated script and cartography. Horns can be simple, or elaborate with battle maps, names and dates. The design can tell a soldier’s story.

Sheets is now a journeyman horner with The Honourable Company of Horners and a master horner candidate. He also attends reenactments as a public history interpreter, informing audiences about the breadth of horn work created over a few hundred years. He shows them the various things a horner can make: combs, hornbooks, spoons, lantern panes, beakers and blowing horns. He demonstrates how various horn items were made centuries ago.

“I also tell them that horn work is NOT a lost art,” Sheets says. “It is alive and practiced by hundreds of hobbyists and even professional artisans.”

A Reluctant Confrontation

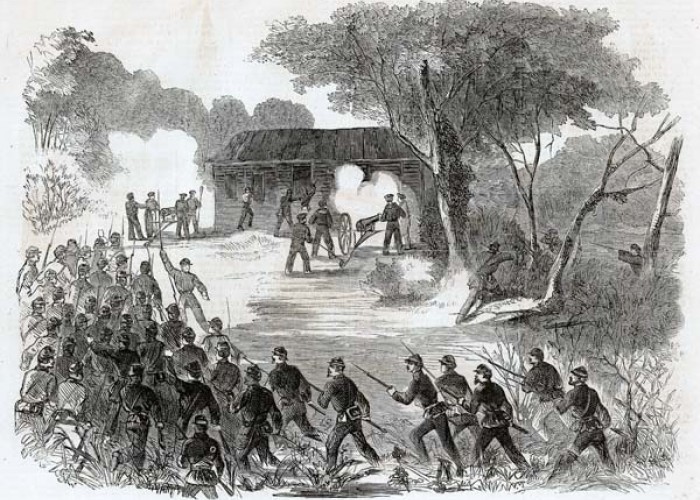

The Battle of Alamance lasted just a couple of hours.

Though angry and passionate about their cause, the Regulators were disorganized. Their leader, Herman Husband, was a Quaker pacifist. Although they outnumbered Tryon’s army by nearly two to one, some Regulators were unarmed.

Tryon’s army was well-trained, equipped with field canons and swivel guns. The confrontation began with one of his soldiers reading portions of the Johnston Riot Act. The Regulators, who were unlawfully assembled, were given an hour to disperse. They responded with shouts of “Battle! Battle!” and “Fire, and be damned.”

Unable to reason with them, Tryon — easy to spot in his red coat — ordered his troops to fire.

Men scurried across the battlefield. There was an exchange of gunfire. Canon blasts shook the smoke-hazed field.

At the end of it, six Regulators were hanged and 12 arrested, concluding the Regulator movement in North Carolina.

But on this day in May, nearly 250 years later, there would be no such violence. Soldiers on both sides would end the evening with a fine meal together and the chance to reenact the battle again the next day.

About the Author

Tina Firesheets is a freelance writer based in Jamestown, North Carolina.-

Brush up on NC history

-

Share this story: