Exploring the Roots of Your Family Tree

By Renee C. Gannon

What began as a quick online search to help with my daughter’s sixth grade social studies family tree project soon turned into a hunt to prove a family story that my maternal side had a connection to famed frontiersman, Daniel Boone.

In my search that evening, I uncovered one online family tree that linked my known Boone ancestors with Daniel himself, or “uncle Daniel” to my direct ancestors. We proudly added Daniel’s name to complete the project.

But something nagged me about the tree. My curiosity plunged me into a months-long search to prove I linked to Daniel’s brother, Jonathan Boon (original spelling), as the tree suggested. But a little more digging told a different story that came down to two John Boons whose families lived in and around Rowan County during the mid-to-late 1700s. One was the offspring of Jonathan, the other became fatherless at an early age. I found many instances of the two Johns causing confusion amongst other family researchers, but finally found the true Boone leaf for my tree.

The answer to the which-John-is-which riddle unraveled a story of a German immigrant named Johan Baltzer Bohn who landed in 1746 Philadelphia on the ship Ann Galley. He soon migrated to North Carolina via southwestern Virginia to raise a family, but died when his children were young. His first-generation American son, John Boon (spelling changed), fought in the American Revolution as a soldier from Rowan County, before settling in Guilford County to raise the next generation of North Carolinians. His descendants didn’t stray very far, with subsequent generations living throughout the central Piedmont area of the state, including myself.

Through the search for my family story, I lost a frontiersman, but gained an American patriot.

Creating a tree

How did I unravel the riddle? I had a basic line going back to the John Boon generation, but which John? I needed verification. I started with myself, my parents and grandparents, writing down full names, birth and death dates, places they lived. I kept my search narrow, just following the Boone surname and its many spellings.

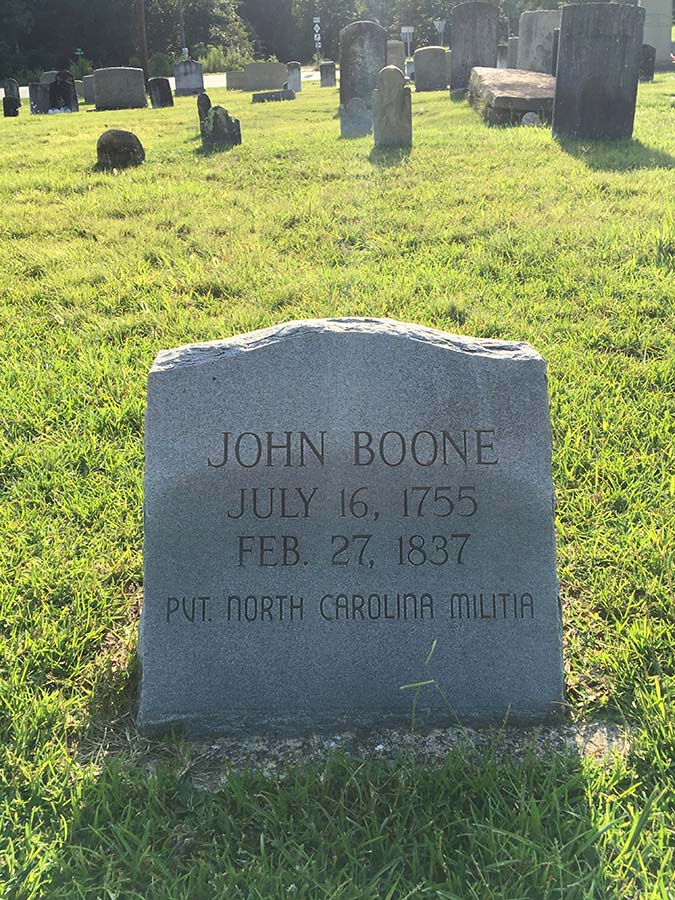

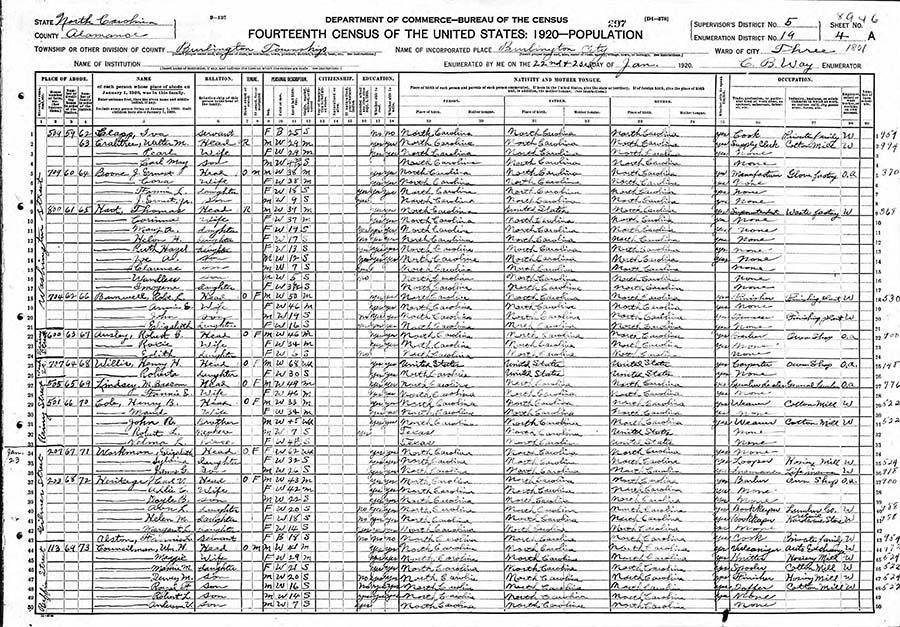

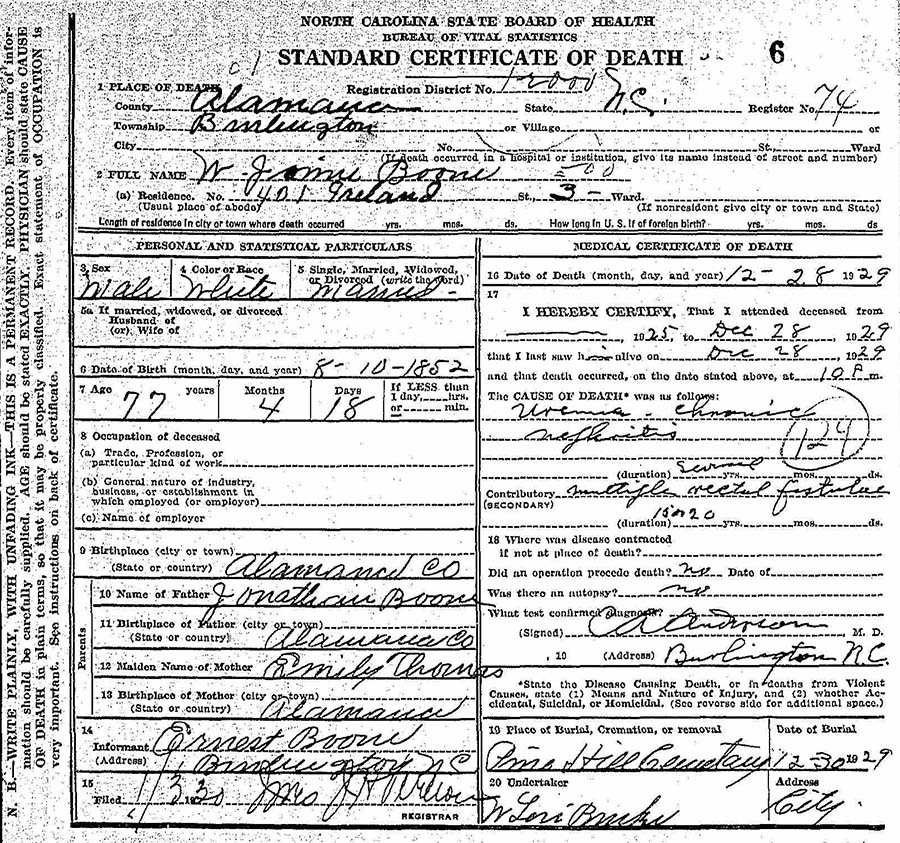

Family bibles, vital record certificates found in files and online, as well as online U.S. Census records at familysearch.org (free) and ancestry.com (paid subscription), helped fill in the tree. At the Alamance County Register of Deeds office in Graham, I searched birth, death and marriage certificates, following the information trail of each generation listed on those documents. A search on findagrave.com (free) located the final resting spot of several relatives, including John Boon — the true John Boon on my tree — buried alongside two of his three wives at a church graveyard in Gibsonville.

Pages from that Gibsonville church’s records contained more clues about past generations, and online War Department pension records held details of John Boon’s war experience.

My Boone genealogy hunt, despite a few unsolved mysteries that I continue searching, was easy compared to others. Beginner family researchers often face many roadblocks in locating records, according to Vann Evans, correspondence archivist for the State Archives of North Carolina.

“In North Carolina, the state did not pass vital records legislation requiring birth and death certificates until 1913,” Evans explains. “Prior to 1868, most N.C. counties did not retain marriage licenses, which give parent names as with the birth and death certificates.”

Evans also notes that women are often difficult to find early on because females were not taxed, did not have voting rights and often did not own property in their name.

“People of African American descent face other unique challenges, especially if their ancestors were enslaved,” he adds.

Other problems include destroyed or lost documents from natural disasters, war, theft and fire; as well as the ever-changing county lines that shifted in the early- to mid-1800s. For instance, what is now a part of Alamance County was once Orange County, so any records during those years would be housed at the Orange County courthouse. These roadblocks and misinformation often found at online search sites can lead to frustration.

“The most valuable asset you can have doing your genealogy is your brain and your ability to analyze, if what you are seeing makes sense and if it’s possible to have happened at that time and at that place,” explains Sheri Liles, a 25-year genealogist veteran and registrar for the General James Moore Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), in Wake Forest. “The second most valuable asset is your knowledge of history. You have to know what was happening in your ancestors’ area at that time.”

Where to search

As I and others have learned, don’t believe everything you find online.

“You can’t rely on any online family tree site to be 100 percent accurate,” Liles says. “Some users just throw information on their trees without checking sources. You must pay particular attention to dates, and verify as best you can.”

But online searches are becoming more fruitful and increasingly accurate. These websites are constantly adding information beyond the basic vital records and census information. The free site familysearch.org has an ever-growing index of records; and ancestry.com adds on average 1 million documents a day. Other subscription sites include fold3.com for military records, newspapers.com and findmypast.com. Google and Bing searches also produce results; and the DAR website at dar.org has an extensive archives section that is open to members and non-members.

“I look at online sites as a two-part option: one is the family trees built on those sites that may give you hints, and the other is the official documents offered to prove the hints,” Liles says. “These sites have millions and millions of records, and all are searchable by name.”

Evans recommends beginner genealogists start at the state’s online genealogy resources, statelibrary.ncdcr.gov and at archives.ncdcr.gov. The State Archives and its Genealogy Room in Raleigh have staff available to assist researchers on-site. Access to the bulk of the archives is free and open to the public. The state library and many of the state’s county libraries offer free access to ancestry.com as well.

“Archival records research, online and in person, can be time consuming and frustrating, but it also is very rewarding when you find that nugget,” he says.

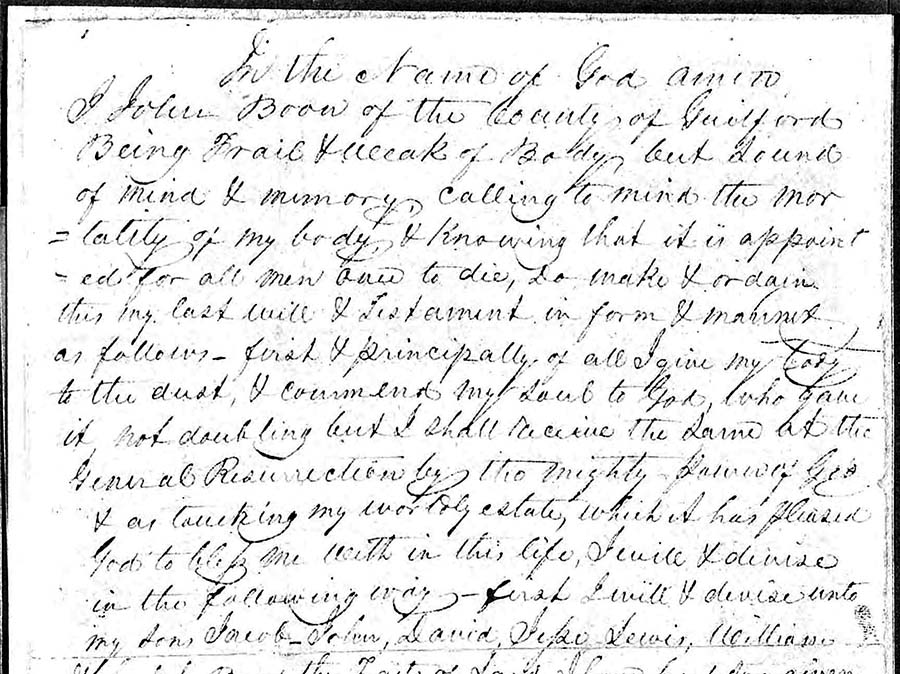

County Courthouse Register of Deeds offices are also available to visit, email or phone when searching for vital records (find N.C. county offices at bit.ly/2bf5wdn). Other records that may help include probate records, wills, estates, burial records, land titles and deeds. Local libraries may also have genealogy information.

What about your family story?

I continue to search and learn more about my Boone family tree. The bits and pieces gleaned from land deeds, wills, vital and census records weave stories about a revolutionary war soldier, farmers, millers, shopkeepers, mill workers, a short-term Confederate soldier, landowners, and yes, slave owners.

Reasons for conducting family research vary. Some just want basics, while others are looking for a personal connection to their ancestors.

“It becomes a treasure hunt,” Evans says. “Most of our ancestors didn’t leave diaries or letters, but we can often gain insight into their lives beyond a set of names and dates by using available resources.”

And don’t be afraid of what you may find.

“My philosophy is that I’m not responsible for what they did, whether good or bad. It’s part of my story,” Liles says. “It’s your family history, how and where they lived. Most people aren’t going to find a famous ancestor, but they do find a story worth retelling.”

-

Share this story: