A Fiery Preacher in the Old North State

A tale from North Carolina’s oldest church

By Tim AllenSt. Thomas Episcopal Church in Bath has been an active parish for more than 300 years. Services are still held in the historic structure every Sunday.

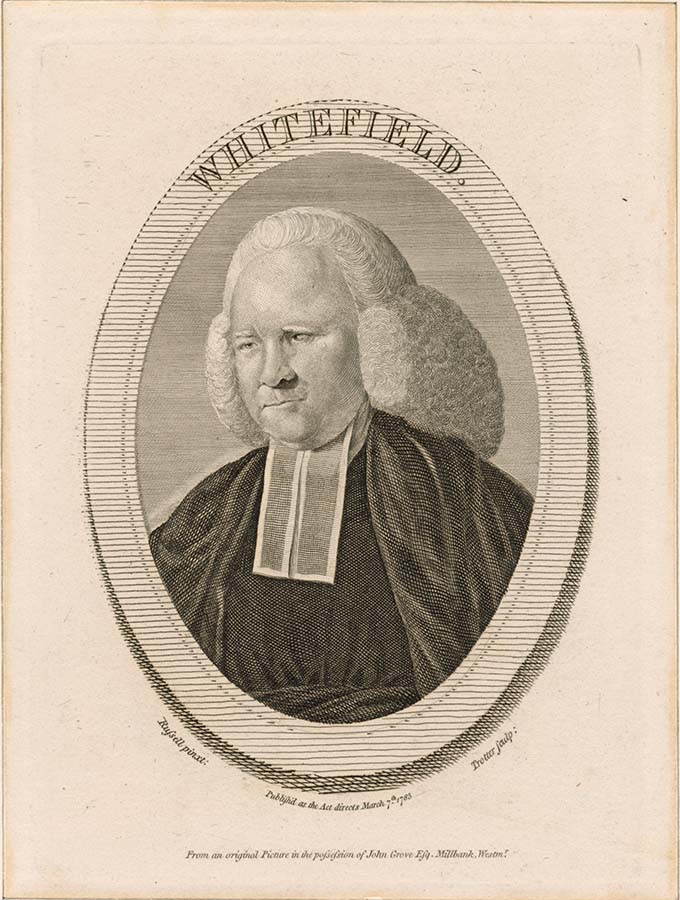

The Grand Itinerant George Whitefield was an Anglican minister from England who excelled in revivalistic preaching that was dramatic, passionate and emotional, often moving many to tears. He made several trips to the American colonies from 1739–1770, and achieved great fame and esteem. Ben Franklin, pretty much an agnostic, was quite taken with him. Whitefield set up an orphanage in the Georgia colony in 1738. He returned to the colonies in 1739 and was a huge success in Philadelphia and New York. But in North Carolina, he encountered a cold welcome.

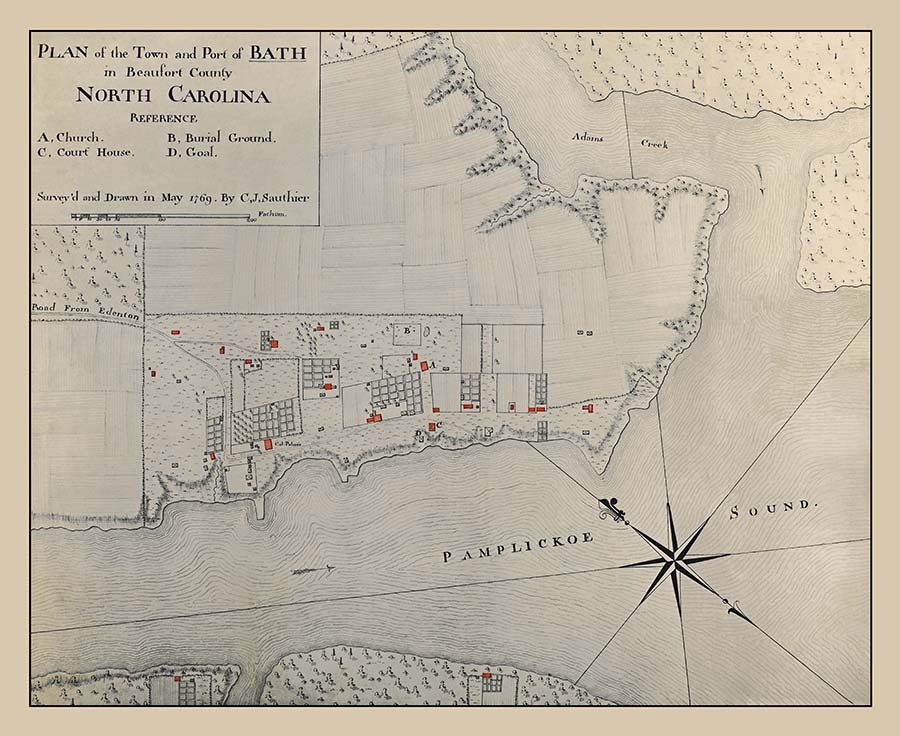

After leaving Virginia and riding horseback on wild and swampy roads in uninhabited territory, he arrived in the Old North State in December 1739. He passed through Eden Town, “a little Place, beautifully situated by the Water-side,” and reached Bath on the evening of December 22. The next day, a Sunday, he preached to a noon-time crowd of 100 people — low for Whitefield, who could draw thousands for his outdoor sermons. Why the lack of enthusiasm?

In a 1743 letter the minister of St. Thomas Church in Bath, Rev. John Garzia, observed, “immorality is arrived to that head among so many, that it requires not only some time but great patience to conquer it.”

The port of Bath had been frequented by pirates — including the infamous Blackbeard, who had called the area home a mere 20 years before George Whitefield’s journey south. It remained a swashbuckling town. The fiery itinerant came down hard on dancing, cursing and drinking, and for the predominantly Anglican audience, this brand of vitriol was not welcome. Neither was Whitefield. In fact, it would be another 20 years before Whitefield cracked the ice of North Carolina’s religious indifference.

After preaching in Bath, Whitefield crossed the “Pamplico River” and stayed over at an “Ordinary by the Water-side” (a tavern that served food). On Monday, Christmas Eve, he arrived at Newborn Town (Newbern) where he celebrated the “Lord’s Nativity” with friends. On Christmas Day, Whitefield “went to publick Worship,” and received the Holy Sacrament from the Church of England minister Rev. John LaPierre, which was celebrated in the “Court-house.” Whitefield, unimpressed by the service, later remarked that he “mourned much in Spirit, to see in what an indifferent Manner every Thing was carried on.”

That afternoon, however, he read prayers to the people and then preached to an attentive and enthusiastic crowd — a marked change from the stolid Anglican service of the morning and more in keeping with the reception he was accustomed to.

“The People were uncommonly attentive, most melted into Tears,” he wrote of the event. From this experience he was excited about the possibilities of revival in the North State. His enthusiasm was premature.

Eight miles outside of Newborn, while staying at the inn of a German family that night, Whitefield reflected in his journal about the day’s events. He was distraught that there was a dancing teacher in every small town yet there was scarce to be found a minister for the people. “…such sinful Entertainments are a Reproach, and will, in Time, be the Ruin of any People.”

Two days later he was in New Town, present day Wilmington. Here he rested until December 30, a Sunday, when he preached morning and evening to a disappointingly small crowd. Whitefield noted that some in the “congregation” were Scottish. (They eventually formed the Protestant Presbyterian Church of Wilmington, now known as First Presbyterian Church.) Having spent a week in North Carolina with little to show for it, from Wilmington he left for South Carolina.

A few days later Whitefield lamented: “In North Carolina there is scarce so much as the Form of Religion. Two Churches were begun for some Time, but neither finish’d. There are several Dancing-masters but scarce one regularly settled Minister.”

In the fall of 1744, Whitefield left the South to return to the northern American colonies. A year later he itinerated southward, but once more he found a “loose” lifestyle of dancing and entertainments perpetuated religious indifference in North Carolina.

In 1747 Whitefield was recuperating in “the ungospelized wilds” around Bath where he wrote in a letter: “I wanted to let North Carolina have as much time as I could.” The aging grand itinerant was beginning to see success in North Carolina. “The barren wilderness was made to smile all the way. I trust good was done in North Carolina. The poor people were very willing to hear.”

Whitefield returned to Bath in 1764. In 1765, according to legend, he was run off from Bath. Whitefield, citing the New Testament, took off his shoes, waved them in the air, shook the dust off his feet and cursed the town of Bath for a hundred years. Yet, according to state archives documents, there is no merit to this myth. In fact, there are indications that Whitefield was treated amicably.

But curse or no, from that day forward the economy of Bath dwindled as ships began porting in other North Carolina coastal cities — especially the more accessible Washington — and the wealthy moved to more prosperous ventures in other areas. A hundred years later, Bath had become the quiet town we know today.

About the Author

Tim Allen is a North Carolina-based author and award-winning professor of history, religion and humanities. His latest book, written with Steve Miller, is “Slave Escapes and the Underground Railroad in North Carolina” (History Press).-

Share this story: