A Lost Shipwreck, Found

Archaeologists are exploring a sunken blockade runner off the North Carolina coast

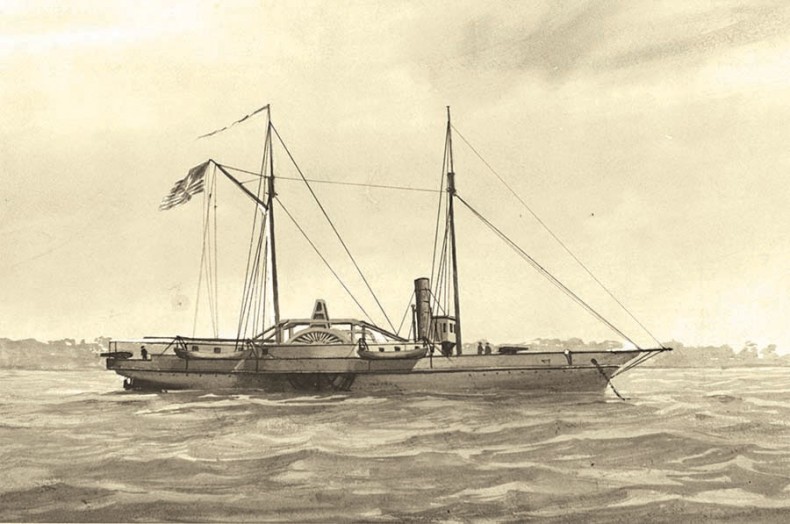

By Joan WennerThe USS Hetzel, a steamer similar to the Agnes E. Frye.

Last February, underwater archaeologists were scanning the seafloor at the mouth of the Cape Fear River when their sonar pinged back a find: A previously lost shipwreck.

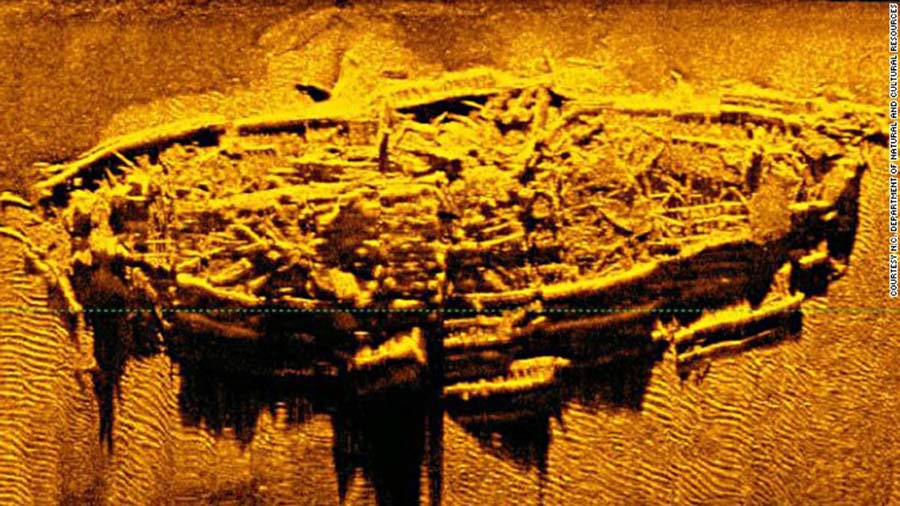

After studying it further, the Underwater Archaeology Branch of the N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources confirmed it to be a 225-foot Civil War-era, iron-hulled blockade runner — bested by Union forces about 27 miles downstream from Wilmington near Fort Caswell. It was the first such find in decades, and it created quite a stir.

“Extensive historical documentation on hand” confirmed the wreck as the Scottish-built Agnes E. Frye (first named the Fox, but renamed by the captain after his wife), one of three sidewheel steamers of its size lost as the Union tightened its grip along the coast to impede navigation and effectively block the flow of Confederate supplies to the vital port of Wilmington. Where columns of conquering Federals once strutted up Market Street, today the Lower Cape Fear Historical Society keeps guard in the restored Latimer House.

The Frye was discovered in a remarkably preserved state, with its hull intact when weather permitted divers to take a closer look. (An 1888 salvage took her two engines and paddlewheel set, though a boiler remains imbedded.) More sophisticated sonar equipment was lent to the effort by Charlotte Fire Department Chief J.D. Thomas, allowing archaeologists to obtain a 3D scan of the Frye.

“The sector scanning imaging technology was the first time put to use at a North Carolina shipwreck site,” explains John ‘Billy Ray’ Morris, director of the Underwater Archaeology Branch and Deputy State Archaeologist, Underwater. “Not only is it faster, it doesn’t require good visibility. The murkiness of the water (along with unsettled currents in the area) hampers divers and investigators.”

Archaeologist Greg Stratton (right) and ECU grad student Hoyt Alexander prepare to dive on the wreck.

The operations were part of a project funded by the National Park Service through the American Battlefield Protection Program. Researchers aboard the vessel Atlantic Surveyor initially recorded the sunken steamer with East Carolina University Maritime Studies Program students assisting in gathering data.

“Changing conditions in the area in recent years have revealed large portions of wrecks 18 to 20 feet below the surface, rising 6 to 8 feet from the sand and protruding that much below,” Morris says. “As activities proceed with this vessel, it may also shed light on her advanced British engine technology of the day.”

Outrunning the enemy

Other foreign-built vessels for the Confederacy of the Frye’s type were to be sent as blockade runners and fitted out as armed warships upon their arrival, thus serving two purposes. Some, however, were completed too late in the war to be of any real use to the South.

The Official Records of the Union Navy note that these blockade runners were far faster than Union cruisers could catch in open water.

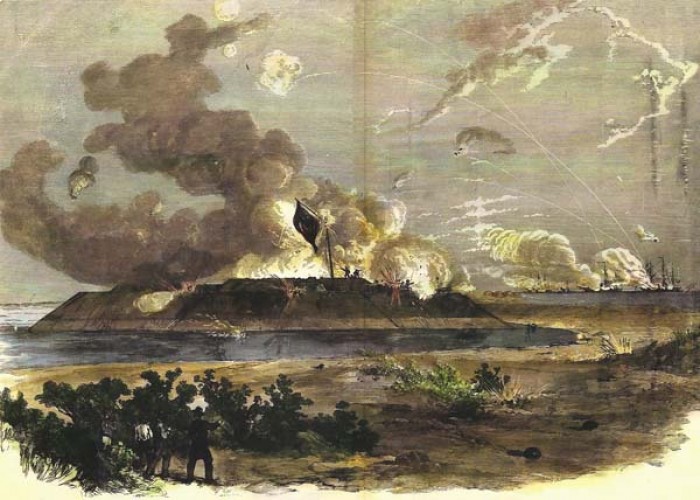

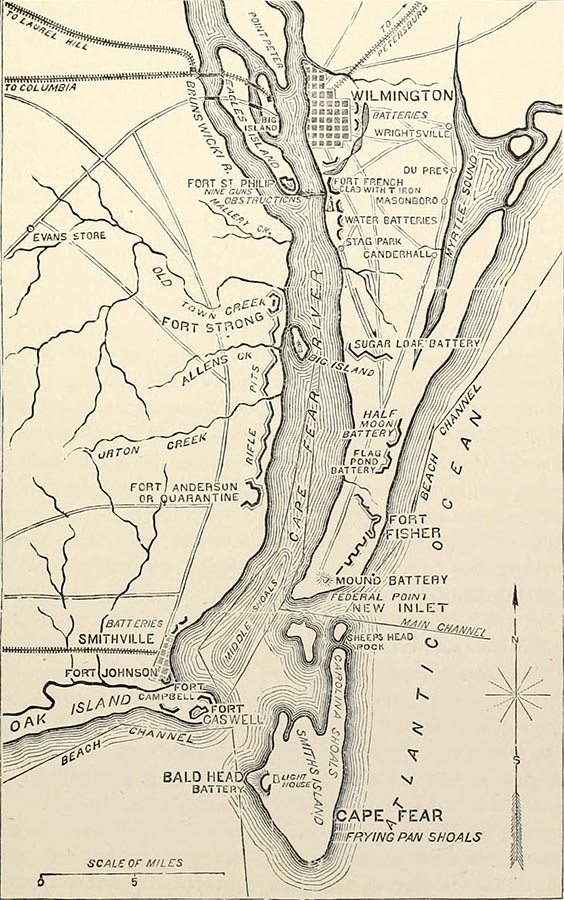

A series of forts and batteries protected Wilmington as the last Atlantic port of trade for the Confederacy, with Confederate steamers racing to make the mouth of the Cape Fear River.

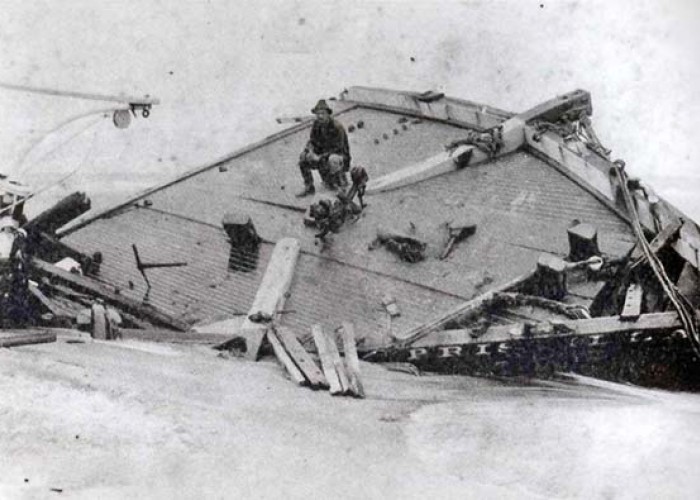

“It is believed the Frye’s crew intentionally ran her aground rather than let the ship fall into enemy hands [as it sank pointing toward the beach], similar to the famous blockade running ‘ghost ship’ Georgiana, when Confederate artillery batteries destroyed her rather than let a Union boarding party reach her cargo of military stores,” Morris says.

To give some idea of cargo potential, some steamers were able to carry payloads of as many as 1,440 bales of cotton on runs to Cuba, Bermuda and Nassau, fetching nearly $400,000 if able to evade capture as a prize of war.

In the U.S. Naval Operations’ archives, a July 1864 communication from Confederate Navy Secretary Stephen Mallory to one of his blockade running commanders instructed it was of the “first importance” that their steamers not fall into the enemy’s hands. To another he commanded the adoption of a “thorough and efficient means for saving all hands and destroying the vessel and cargo whenever these measures may become necessary to prevent capture.”

It was good advice. On December 1, 1864, a British blockade runner was captured off Cape Fear with all her cargo, including munitions, which the Southern army desperately needed. A week later, another was captured.

In his last annual report to President Abraham Lincoln, the Federal Navy Secretary noted the great impact on the Confederacy made by Union sea power in “an undertaking without precedence in history,” with “65 steamers captured or destroyed endeavoring to enter or escape from Wilmington.” He noted that the U.S. Navy had grown to 611 ships “and by December had taken a large number of prizes.”

A new era for the Frye

Artifacts retrieved from the Frye, including personal effects, are expected to be exhibited at the Fort Fisher museum at Kure Beach, so stay tuned. A conservation plan and a budget are being developed. A national historic landmark and popular North Carolina Historic Site, the fort helped keep the port of Wilmington open for many blockade runners as the last remaining supply line to General Robert E. Lee in 1865.

“There are some kinds of knowledge and understanding that can only be acquired through immersion and participation,” says Kevin Cherry, North Carolina Deputy Secretary of Cultural Resources. “Historic sites seek to provide the environment for that kind of learning.”

Fort Fisher State Historic Site

1610 Ft. Fisher Blvd. South

Kure Beach

910-458-5538

nchistoricsites.org/fisher

Once retrieved, artifacts from the Frye will be exhibited at the Fort Fisher museum. Admission is free, but check online for hours and exhibit updates. Make it a full day: The North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher is just down the road.

About the Author

Joan Wenner, J.D. is a longtime Civil War history and maritime writer who currently lives in Pitt County.-

More NC history from the high seas

-

Share this story: