Wartime on the Outer Banks

Remembering life on the NC coast during WWII

By Story and photos by Leah Chester-DavisOn a soggy spring morning last year on Ocracoke Island, the clouds gave way to sunrays just as the plaintive tunes of bagpipes beckoned islanders and visitors to a small cemetery. Tucked back on a quiet spot on British Cemetery Road is the plot where four British sailors were laid to rest in 1942. They lost their lives patrolling and defending shipping lanes off the Carolina coast during World War II.

Each year, islanders and visitors gather to remember their sacrifice, and 2017 marked the 75th memorial service. The day before, islanders, special guests and dignitaries had gathered on neighboring Hatteras Island at the Buxton British Cemetery for a memorial observance for two British sailors who washed ashore there during World War II.

Unbeknownst to many, German U-boats, or submarines, plied the waters just off the Outer Banks of North Carolina during World War II. Their intent was to disrupt busy sea lanes up and down the Eastern Seaboard, particularly off the coasts of New York, Cape Hatteras and Florida. The Germans sunk nearly 400 merchant vessels headed to England with badly needed food and war material, earning the area the moniker Torpedo Junction and contributing further to the area known as the Graveyard of the Atlantic.

U.S. Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall was quoted as saying in June 1942, “The losses by submarines off our Atlantic Seaboard and in the Caribbean now threaten our entire war effort.”

Frieda French and Thomas Cunningham

British sacrifice, remembered

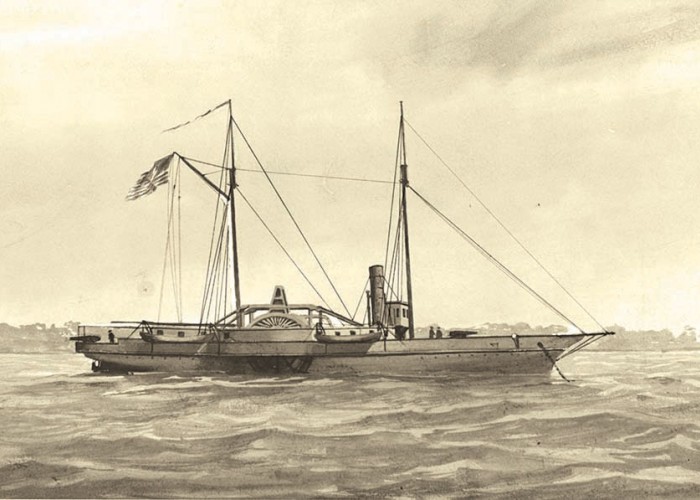

Because the United States was new to the war effort in 1942 and the eastern seaboard was quite vulnerable, the British Royal Navy provided a flotilla of 24 trawlers to patrol the coast for German submarines. The HMT Bedfordshire was one of those ships. On May 11, 1942, it was torpedoed by a German submarine and sank about 40 miles south-southeast of Cape Lookout. All of the sailors on the HMT Bedfordshire were killed.

The bodies of two, Sub-Lieutenant Cunningham and Ordinary Telegraphist Second Class Craig, washed ashore on Ocracoke. Two other bodies were later found and remain unidentified.

Frieda Gray French, now 81, was just six years old at the time. Her father, Homer S. Gray, was chief of the Coast Guard base on Ocracoke. “He was the one they brought the bodies to when they washed up on the shore,” she said. “He helped bury them.” They were buried with military honors.

French, who lives in Elizabeth City, traveled to the 75th memorial ceremony to pay respects and to meet Thomas Cunningham, the son of one of the British sailors whom her father buried. She and her daughter, Sharon Stanley, talked about how meaningful the ceremony was.

Chief Homer S. Gray. Photo courtesy of: Frieda French

“I really wanted Mom to meet Mr. Cunningham,” Stanley says, looking back on the ceremony. “I thought it was pretty neat that 75 years later the children [of the Coast Guard officer and a British sailor] could meet. People would not believe how much the military and the community did for that memorial service. There were a lot of dignitaries who flew in. It was very impressive.”

Among those participating in the 2017 ceremonies were representatives from the U.S. Coast Guard, the Canadian Forces Naval Attaché, the British Naval Attaché, the National Park Service, the U.S. Coast Guard Pipe Band and Coast Guard Auxiliary, the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum, schools, and Boy Scout and Girl Scout troops.

French says she remembers as a child being at an older neighbor’s house in Avon and wanting to go home. “She said you can’t, because the Germans are hiding over in them woods,” French recalls. “I never forgot that.” It was in the evening and her neighbor was concerned about using a lantern. “She was afraid.”

At that time, residents on the Outer Banks adhered to a blackout policy to avoid being spotted by the Germans. While there were rumors about Germans being on the island, the Germans that French’s neighbor spoke of were likely on submarines off the coast.

Carroll Gray (center) and James Gray (right)

Witnesses to history

Brothers James and Carroll Gray, Cape Hatteras Electric Cooperative members, also attended the British Cemetery Ceremony on Ocracoke for its 75th anniversary. Though they are not related to French, their father, who also was in the Coast Guard and served at Buxton, knew hers.

World War II hit close to home for the Gray family. Their father, Cyrus Gray, was among the first contingent to land on Guadalcanal, part of the Pacific theater and the first major offensive by Allied forces against Japan. His ship was torpedoed and he was badly burned, hospitalized for about six months before being sent home to North Carolina.

When the Gray brothers were 10 and 11, they witnessed the burial of two British sailors whose bodies had washed up near Buxton. The men were from the San Delfino, a British tanker.

“I was at the grocery store in the village to pick up an item for my mother,” Carroll remembers. “Somebody mentioned they heard that a sailor had washed up and the funeral was going to be the next afternoon. I went home and talked to Jim, and we decided since we had never been to a funeral and had never seen a dead person that we would go. We snuck off and walked out to the beach to the service area. We were the only civilians, except for the minister, out there.”

While word of two sailors washing ashore was big news, the brothers explained that many people weren’t aware of the war being so close to the Carolina coast.

“Generally, it was a pretty well-kept secret I think as far as the information that all of these ships were being sunk,” James says. “My brother and I walked the beach fairly often, and you could see the ships because they were running fairly close to the beach to stay away from submarines. It was not unusual to hear an explosion when a ship got torpedoed.” “You would go out the next day and you would see it burning and sinking,” says Carroll. “We went out a lot of times just to look for debris on the beach. That is where I first became aware of instant coffee. There were thousands of little round cans, like snuff cans I guess. The instant coffee washed up on the beach and all kinds of other debris.”

“A lot of oil was shipped in five gallon buckets. A lot of times we would salvage the five gallon cans of oil and drag them across the beach and then sell them,” James adds. “We got 50 cents for a five-gallon can of oil from the local stores.”

In addition to families using blackout curtains at night, James says anyone who had a car painted the upper half of the headlights black so they wouldn’t be seen from a distance.

“There were an awful lot of ships sunk off the coast here,” James says. “Most of them were at night, and they were loud enough to wake you up.”

About the Author

Leah Chester-Davis loves to explore North Carolina. Her business, Chester-Davis Communications (chester-davis.com), specializes in food, farm, gardening and lifestyle brands and organizations.-

More North Carolina Naval History

-

Share this story:

Comments (3)

Sharon Stanley |

May 31, 2018 |

reply

Leah Chester-Davis |

June 05, 2018 |

reply

Ricky Guantanimo |

December 07, 2018 |

reply